Some reflections on transitioning out of being a "young composer"

What is the cut-off for being a “young composer?” Everyone defines that line a little differently, but I’m in my mid-30s, and in my case anyway, I certainly feel like I’ve moved onto the next thing.

This transition is more a state of mind than anything else. Over the past few years, when I’ve found myself in young composer settings, I’ve gotten that awkward feeling of being somewhere you no longer belong, like when you visit your old high school a few years into college.

Also, much to my amazement, I’ve found myself confronted on occasion by composers younger than me asking for career advice. Thinking back on the past few years, I suppose I did learn a few things that would have been useful to my 20-something self. So in the spirit of paying it forward, here are some reflections on composing after young-composer-hood.

What you did in your 20s won’t matter much

There is a cult of youth in the composition scene, just as there is with most public-facing human activities. When you’re a young composer, a lot of people are interested in what you’re doing simply because “young composers!” That’s not wrong—young people with no track record do need a way to get a leg up—but the mistake is assuming that the attention you get as a young composer somehow predicts the attention you’ll get when you’re older.

After a few years, most of the people who experienced your youthful glories will have totally forgotten that you exist, having moved onto the next round of young composers. So while you should definitely take advantage of the young composer competitions, festivals, workshops, and prizes, it’s important to realize that there’s an expiry date on their usefulness.

Composing is about who you know

Speaking of prizes and festivals and such, it turns out that winning them is much less important than the connections you make along the way.

When you’re in your 20s, the task of finding compositional opportunities mostly gets sorted out on its own: you have to write pieces for student recitals, you go to summer festivals, you get a few emerging composer commissions, etcetera. This is also, not coincidentally, the period in your life when you reach “peak friends.” Opportunities arise seemingly organically, maybe you win a few prizes, and it’s logical to assume that all this is happening because you write good music.

Then a few years pass. You’re no longer in school, you’ve aged out of the young composer festivals, and having passed peak friends, a lot of people move on and lose touch. It then becomes obvious that the main reason you’re composing for Quartet XYZ is because the cellist is a buddy of yours, not because of your skill as a composer. Yes, you do also have to be a good composer—but there are a lot of good composers out there, so people tend to work with their friends. While there are exceptions to this pattern, most of your post-20s opportunities will stem from the personal relationships you make.

When I was in grad school at UCSD, I got my fair share of those young composer commissions and prizes. Also, as a Canadian I didn’t expect to stay in the US long term, so while I did of course make friends at school, my priorities were always elsewhere. Well, here I am in San Francisco almost 10 years later, married to an American. Yet few of my professional connections today stem from grad school, probably because my peers could tell I wasn’t fully invested in the community. And for all the effort, Gaudeamus and MATA and the prizes I won never created any lasting opportunities. In retrospect, back then I probably should have spent less time sending out applications and more time just hanging out with people.

A lot of your peers will stop composing

Look around: how many of the composers that you know are in their 20s? Then think about how many you know in their 30s. It’s a smaller number. Move up to 40s and it shrinks again. With each passing decade, there are fewer people who continue to compose. It’s a hard lifestyle, opportunities are not always forthcoming, and faced with the task of toiling in poverty versus getting an office job that actually pays, many people choose the latter.

You need to keep proving yourself

I’m a recluse by nature—I’ve always dreaded schmoozing and networking, or really most types of group-based social activity. But in my 20s, I expected that if I stuck it out for awhile, eventually my reputation would make it less necessary to do that stuff; that opportunities would come my way with increasing ease. Turns out that’s not the case. You need to make more of an effort as time goes on, not less, and you need to create more of your own opportunities.

At some point in your life, while you’re busy being a young composer, you’ll suddenly realize that an active cohort of younger young composers has sprung up after you. They will be mostly unaware of what you were doing in your 20s, because they were teenagers then. They’ll also be busy basking in the cult of youth and hanging out mostly in an echo chamber of people their own age.

Simultaneously, more established musicians will have started to forget about your young composer successes, since there’s a new group of up-and-comers to attend to. You’ll also have fewer colleagues your own age to hang out with as people drop out of music.

The end result is that you have to keep proving yourself, just like you did in your 20s. Except now, you also need to create all of the opportunities for yourself. There are no prizes or festivals or required recitals to rely on. You have to form an ensemble, or put on concerts, or pitch ideas to the groups your friends run, or otherwise use your personal network to find ways to create music. At least this has been my experience so far in my 30s, who knows, maybe it will actually get easier given another decade. But I’m not holding my breath.

You achieve greater success by helping others succeed

Which brings us to the next point. When you pursue projects that are exclusively about your own glory, you will have to do everything yourself and pay full price for services. People will play your gigs, but since they’re not invested in your success, it’ll just be another gig for them.

In contrast, if you design your activities so that they help others achieve their goals as well, they will want to help you succeed. You will find that you have a network of people eager to assist you with the things you care most about, and you’ll be able to mount your projects with greater ease than you could have on your own.

Making money and making music are unrelated questions

There are a lot of ways to earn a living, just as there are a lot of ways to compose music. You can follow the academic path. You can teach privately. You can conduct or take gigs as a performer. You can do a job outside of music, or as an arts administrator. Maybe if you’re lucky you’ll start an ensemble that taps into big philanthropic dollars.

There will be some overlap between the money aspect and the composing aspect, but the connection will never really be as strong as you want it to be. In my 20s, I was fairly successful as a grant writer and freelancer. I assumed that this success would continue to expand, both in terms of volume of commissions and remuneration.

What I discovered, however, is that there is an upper bound. There are only so many funders, and you can only write so much music. Therefore, as your financial needs increase—and they will, don’t fool yourself into thinking you can live like a college student indefinitely—you need to find other income streams. My income from grant writing and commissions has stayed fairly steady over the past decade, but it has become a smaller proportion of my total income.

You have to work from a place of strength

Andrew Solomon perhaps put this most poetically in his Advice for Young Writers: “To know more is simply a matter of industry; to accept what you will never know is trickier.”

When you’re young, there’s the tendency to want to do everything, learn as much as possible, conquer all challenges. I used to drill and drill and drill on ear training exercises, because as a percussionist, I felt like I had to “catch up” to the composers who grew up playing strings or singing and had amazing senses of pitch.

I did get a lot better, but I don’t play pitched instruments every day, so those skills are just never going to be as good as someone who does, even if I did have the time to keep up the ear training drills.

So I compose from my strengths and interests, accepting that there are things others will do better than me and that there’s nothing I can do about it. I’ve got the right skills for the music I want to write, and that’s what counts.

This principle likewise applies to the career aspects of composing. You need to focus on the types of auxiliary activities that you’re good at and enjoy. The reason I’m sitting here writing this article is because I like to write, I’ve gotten decently good at it, and I’ve attracted a respectable audience over the years. If those things weren’t true, I would be doing something else instead.

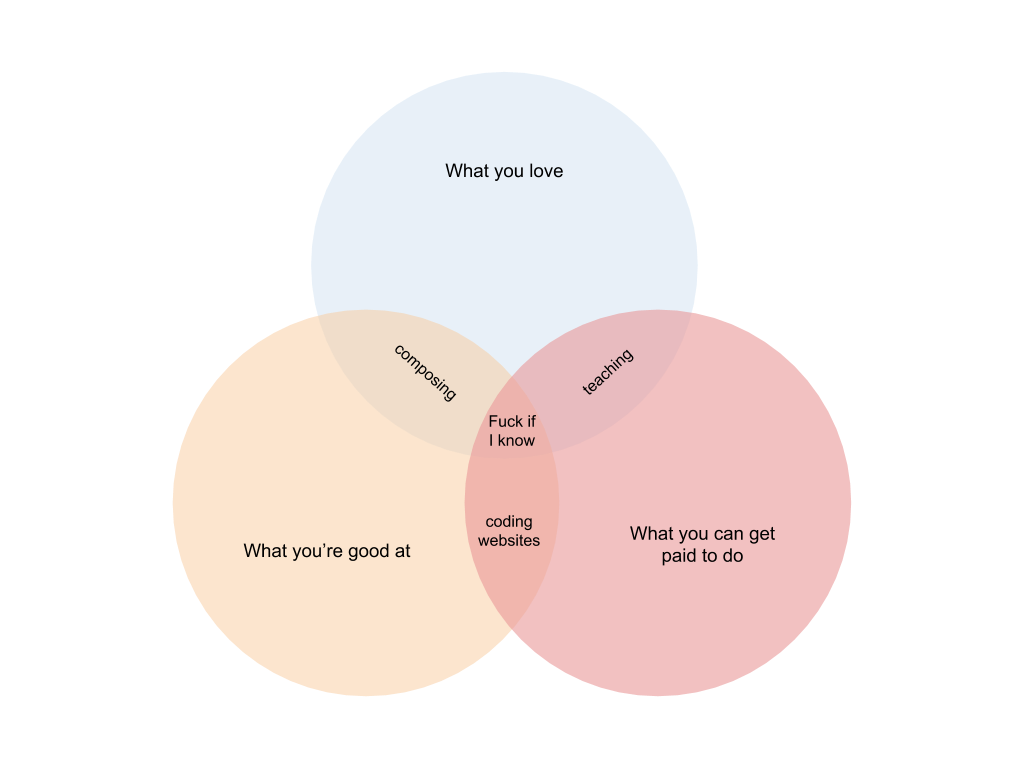

Vocational counselling for composers…

You need collaborators

Because you’re working from a place of strength and can’t do everything yourself, you need find people in your life who can support your weaknesses. This arrangement could be formal or informal. A lot of great people throughout history have had spouses or patrons that have kept them afloat, both financially or just in terms of keeping their shit together. Some composers start collectives or ensembles, or they work with dance companies or otherwise find a team of people to support them. Note that this doesn’t have to be an egotistical, “taker” kind of arrangement. In fact, it’s usually more successful if it’s reciprocal. But you need to find your complements and work with them.

You won’t go to all the concerts anymore

It’s Friday afternoon and you’ve been (working/teaching/grant writing/rehearsing) all week, haven’t seen your (spouse/kids) for more than a few minutes a day all week, had a (board meeting/fundraiser/computer meltdown) last night and have (no groceries/a piece due next week/relatives coming over tomorrow). There is a new music concert tonight, and they’re amazing players that you love, but they’re playing Boulez (or whoever) and you’ve just never really been that into Boulez. You will skip the concert to watch Netflix and have a beer, guilt-free. Otherwise you’ll soon burn out on all concert going, and if you don’t enjoy concerts, it’s pretty hard to stay motivated to compose. I suspect that going to boring concerts is the #2 reason why people stop composing. (#1 is of course the money.)

Your best artistic days are ahead of you

This article by Irish/South African composer Kevin Volans caused quite a stir recently, and there’s a lot in it I disagree with. But one thing he said that is undoubtedly true is that people become better composers over time.

Young composers, on the whole, write conservative music that lacks depth and personality. There are Mozartian exceptions, but even the best young composers tend to get better with age. You’ll write better music in your 30s, even though you’ll likely get less recognition for it seeing as you’re not a “young composer” anymore.

You have to be OK with a lack of feedback

Chances are, you’re no longer in a structured environment like school or the young composers summer circuit, so you won’t get a lot of feedback on your work, except for reviews of your performances here and there, or complaints from your parents about why you can’t just write prettier melodies. You have to be OK with not having anyone comment on your music most of the time.

This is an especially composerly issue. Playwrights tend to work with dramaturges for this very reason, professional singers often have coaches, and there are many other parallels across the arts. But it’s hard for composers to find this kind of collaborator. It’s just going to be you most of the time.

You’ll probably be a much faster composer

The reasons why you write music will become clearer. (If they don’t, you’ll probably stop composing.) When you know the why, and you have more practice with the how, the act of composing speeds up quite a bit. That doesn’t mean you’ll never get stuck, just that the average number of hours you need to put in to create a given amount of quality music will go down.

That will give you time for other things, like hobbies, or volunteering, or having kids—whatever. Take advantage of those possibilities. They’ll lead to a richer life, and the best art always stems from lived experience.

Originally published on New Music Box >>