No seriously, there's no such thing as arts entrepreneurship

Not everyone buys my claim that entrepreneurship is impossible in art, so I want to spill a few more pixels on this question. Whether or not you agree with me, you’ve got to admit that entrepreneurship hasn’t been a winning formula for artists as a whole—unsurprisingly so when you examine the fundamental characteristics of both disciplines. Art is infinitely scalable, communal, inherently subjective, and useless by design. Entrepreneurship is scarcity-based, individualistic, inherently objective, and pragmatic by design. Both are creative activities, but of opposite types.

When you look more closely you’ll notice that “art entrepreneurship” is and has always been about art technology, not art itself. This was as true for 19th-century sheet music publishing as it is for 21st-century online music streaming. Entrepreneurs build business models around a technology, then art serves as an input for those models—there’s always that technological bridge. This distinction matters, because we live in a time that is not particularly sympathetic to the arts, and simultaneously many of the business models we’ve come to rely on have been upended. It’s important to try to understand what’s actually going on so that we can find approaches that work.

Pro athletes and supermodels

Thanks largely to communications technology, the arts increasingly fall into what economists call a winner-take-all model. Traditionally, you see winner-take-all in areas like pro sports, Hollywood films, Top 40 music, fashion modeling—basically, whenever the needs of the masses can be met by a small group of elite performers. For example, millions of people can watch baseball on TV without the spectator experience suffering in any serious way. That’s why major league players become millionaires while their compatriots in the minors, just one step below, currently find themselves suing the league for allegedly paying less than minimum wage. What’s to blame for this situation? The technology of broadcasting, and the business models that evolved around it.

Winner-take-all has a long history in the arts as well, but the Internet has expanded its reach. There used to be technological constraints on art access: you had to buy a book of Picasso prints, or an LP of Beethoven symphonies, etc. Today, anyone can instantly access photos of Picassos, videos of Mikhail Baryshnikov, or recordings of pretty much anything. Of course, a low-fi MP3 is not the same thing as a 24/96 studio recording, but that’s besides the point. Online streaming and digital photos are “good enough” for most people’s needs, just as watching a baseball game in a sports bar is “good enough” to disincentivize most people from tracking down the local farm team.

People still place value on attending live sporting and music events of course, and that tempers the winner-take-all curve a little, but technology also shifts the baseline for effort. Scarcely a decade ago, if you wanted to hear a specific piece of music, your choices were to go down to the record store or go out to a concert. Both involved leaving the house, physically traveling somewhere, and opening up your wallet. Since you can now hear most anything for free on YouTube, the business model for live music has changed, from “going to hear music” to “attending a special event.” Whether you’re talking about a music festival like Coachella, a superstar performance by Bob Dylan or Renée Fleming, an indie band on tour, or your kid’s cello recital, it’s the “specialness” of the event that makes people spend extra money and effort, not the fact that there’s music going on. Or to turn things around, the need for specialness is why playing in a run-of-the-mill cover band is no longer a feasible way to pay for college.

Not everyone is special

Specialness in music typically stems from the reputations of the musicians and/or venues—or, stated in business terms, from their brands. But brands are not business models, brands are inputs to a business model. Bob Dylan’s brand today is not fundamentally different from what it was back when you could actually pay for college by playing in a cover band, and he still uses it to put bums in seats at a profit. Of course, playing a stadium gig is hardly an original business move, but it works because Dylan is special: you don’t need an innovative business plan when your voice is the emblem of an entire freaking generation.

Note that we don’t think of Renée Fleming and Bob Dylan as entrepreneurs (or Barry Bonds or Albert Pujols), despite the fact that they have valuable brands. They didn’t get to where they are by designing business models that were better than those of their peers, nor did they undercut the prices of competitors, find niches that were undeveloped, or discover more effective ways of delivering vocal music (or baseballs). Yet for some reason, we have a completely different standard for non-stars. If none of the superstars rose to the top through entrepreneurship, why do we preach this path to everyone else?

Competing in a winner-take-all system does not require entrepreneurship, it requires exceptional talent, perfect timing, and a healthy dose of good luck. In fact, entrepreneurship is counterproductive in winner-take-all, because it distracts you from the goal of becoming world-class in your vocation. The presence of a winner-take-all system implies that there is a single superior business model, and the only thing left to do is get good at playing the game.

Later on, once you’ve got a brand, you can use it to get into all sorts of entrepreneurial mischief if that’s your thing—Jay-Z started a popular clothing line, after all. But it doesn’t work the other way around. You don’t develop a brand as an artist by launching a textile import business. And if you stay purely within the arts, the only entrepreneurial paths are the ones that improve art technologies: cheaper recording devices, more effective digital distribution, streamlined broadcasting, improved instrument design, a better eBook suggestion algorithm, etc. etc.

Molecular gastronomy and neolithic cavemen

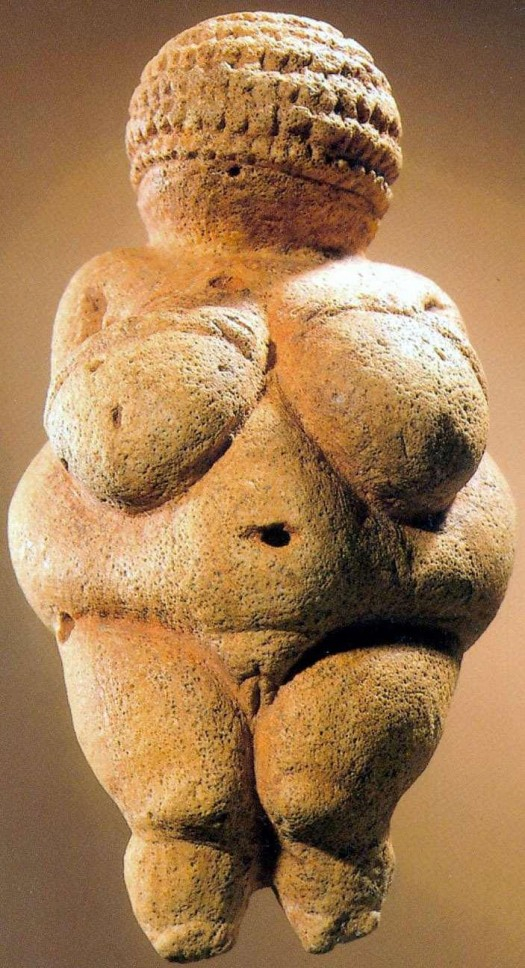

The inherently communal nature of art also poses problems for entrepreneurship. Let’s recall that there were no iPods in the neolithic, and that only very recently has it become possible to experience art without running into other humans. Art exists to bond groups together in a shared sense of camaraderie—that’s how it fits into evolution. Our cave-dwelling ancestors sang songs, danced in rounds, and painted on stone walls because these activities made the people in the group more willing to chip in toward the common good, which in turn gave them a competitive advantage.

This creates problems for entrepreneurship. At the core of all entrepreneurial activity is the concept of functional improvement: doing more with less. Entrepreneurs take something we were doing anyway and do it more efficiently (mass-produced clothes vs. bespoke tailoring), or they find a new thing to do that replaces the need to do the old inefficient thing (buying Coca-cola in bottles instead of visiting the local soda jerk). Then they skim a bit off the top for their own profit.

Art, however, stops being able to facilitate group bonding when it gains a function. That’s because functional activities, by their nature, can be hijacked to benefit the individual at the expense of the group (think serfdom, oil monopolies, predatory mortgage lending). When you add function to art, you get propaganda or advertising. The possibility of corrupted motives makes us distrust these forms; it makes them “not art,” because they are preying on our love of group bonding.

Conversely, whenever art is applied to functional activities like making clothes or cooking food, we always find a layer of uselessness superimposed for the sake of making it art: you wouldn’t call the paleo diet art, but you could say that modernist cuisine is. The difference is that a diet is about a functional goal (better health, losing weight) whereas a cuisine is about group bonding. After all, there’s no functional need for dining to be enjoyable or to represent your ethnic background, it just has to keep you alive.

Given that entrepreneurship and art have mutually exclusive requirements, any entrepreneurial ambitions have to take place entirely within the industries that support art. For example, amplification technology allowed the now-ubiquitous guitar-based rock format to compete with the much more expensive big band configuration. Since the business model was the same (fill a venue with dancing partygoers), the big bands of the ‘30s and ‘40s largely gave way to the rock bands of the ‘50s and ‘60s, who in turn gave way to DJs a few decades later—all thanks to technology, not art. And notice how each technology requires fewer human artists to achieve the same result—that’s entrepreneurship at its purest.

Music wants to be free

Efficient communications technologies like the Internet raise the stakes to new highs. When you turn on Pandora, it’s “your” station, even though you probably didn’t make any of the music it plays. Why? Because you’re appealing to group bonding: the collection of music reflects the tastes of “people like you.” Similarly, the way you dress is “your” fashion sense. So let me ask you an odd question: should you have to pay for the right to have a fashion sense or a taste in music? Of course clothing costs money to produce, and the idea of paying for it is noncontroversial. But people would undoubtedly take offense at paying an ongoing royalty to Ralph Lauren for the privilege of appearing in his fashions.

This is where online streaming runs into trouble. The value of music or fashion, according to most people’s intuitive sense of fairness, should primarily represent the fixed costs of getting it to the user: pressing a CD, buying fabric, etc. When the overwhelming majority of the price goes toward intangibles (e.g. $2000 handbags, royalties for music streaming), people feel ripped off. I suspect this has to do with the whole group bonding/artistic corruption thing: if someone is pulling in sky-high margins on the art itself, then there must be something inauthentic or propagandist about it. In an ideal world, the “art” part shouldn’t cost anything, because its value falls outside of money.

Nor is this attitude confined to Joe Consumer. When artists get paid you’ll witness an elaborate social choreography between artist, payer, and the artist’s peers, all designed to make it seem like a generous and unexpected gift has been presented. When a new art project is discussed, formal contracts typically only get brought up as an afterthought, at the last minute—if at all. When it comes time for an artist to negotiate financial arrangements, every request is couched in apologies and handwringing. You also see this phenomenon at work in rants like this VICE article, penned by singer John Liam Policastro, who is of the (idiotic) opinion that asking your fans for $50,000 via Kickstarter to record an album is unacceptably greedy.

Hans Abbing studied the issue of how artists handle financial negotiations related to their art in Why Are Artists Poor? and found that those who adopt a straightforward manner have more trouble collecting fees, are not liked by other artists (c.f. John Liam Policastro), and receive fewer invitations to create/present their art. It’s seen as untoward for artists to debase their work by crassly quantifying it in dollars and cents, and if they break that rule other artists will be the first to crucify them. Any profit beyond covering fixed costs should be accidental: people throwing money at you because they are so enamoured by your art or some such.

To add fuel to the fire, humans are notoriously bad at calculating fixed costs, even for entirely tangible goods like breadmakers, let alone online streaming. Restaurateur Jay Porter advocated in Slate recently for a higher minimum wage precisely for this reason. The Burger Kings and Taco Bells of the world can offer low prices because the scale of their operations creates supply chain efficiencies that small restaurants can’t access. A higher minimum wage would boost fixed costs across the board, so those advantages become proportionately less, which helps small businesses to compete. Unfortunately, for something like online streaming, the fixed costs are close to zero making this strategy impossible. Meanwhile, artists are forced to battle the deep-seated cultural aversion to paying for the intangible portions of art.

| Low Minimum Wage | High Minimum Wage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate | Local | Corporate | Local | |

| Labor | $1.00 | $1.00 | $5.00 | $5.00 |

| Ingredients | $1.00 | $4.00 | $1.00 | $4.00 |

| Total Cost | $2.00 | $5.00 | $6.00 | $9.00 |

| Difference in Price | 250% | 150% | ||

What this means

On virtually all fronts, art is immune to entrepreneurial impulses. First, technology has removed most of the barriers to infinite, free distribution of art, which creates an extreme winner-take-all market. Second, art is functionless by necessity, and any attempts to add function to it (propaganda, advertising) are treated with suspicion. Third, there is the ingrained expectation that art is somehow outside of money, that artists shouldn’t discuss their art in monetary terms, that the starving artist is purer or better than the wealthy one, etc. Fourth, people have no idea what the fixed costs of art consumption should be, and they resent any attempt to make them pay for perceived intangible costs.

Fine, you say, but does it really matter if by “art entrepreneurship” we actually mean “art technology entrepreneurship”? Absolutely. The conflation creates impossible standards for artists and forces us to expend a lot of energy on activities that are doomed to fail. To give one example, our collective entrepreneurial love-on is the main reason that private American philanthropic organizations increasingly measure the success of an art project in terms of audience attendance. This conflates skill in marketing with skill in art, which then creates a tendency toward middle-of-the-road, unadventurous work: McDonald’s sells a lot of hamburgers, but that’s not because the Big Mac is the pinnacle of culinary achievement.

If you want to require artists to work with promoters/marketers, that’s fine, but don’t make the marketing plan the standard by which you judge the art—help promising artists find the right promoters instead! Any cursory look at art history shows that popularity at the time of creation is a poor measure of long-term success. Vincent van Gogh was virtually unknown during his lifetime, sold a grand total of one painting, and lived off the charity of his brother. J.S. Bach was a small-town organist with nothing but a local following, living under the shadow of Handel and forgotten for almost a century after his death. And lest we forget, the Monkees and the Beatles were about equally popular in the ‘60s.

Another problem is that winner-take-all is not a very efficient model for society. For every wealthy superstar, there are thousands of exceptionally talented artists that didn’t get the right breaks. It’s cruel to sell them the lie that, if only they’re entrepreneurial enough, they’ll get to the top someday too. More likely, they’ll toil in obscurity forever, wasting their potential contributions to society. The myth of arts entrepreneurship serves only to sweep the larger issues under the rug.

Instead, we should strive to put the creative energies of the non-superstars to better use. On the side of art technology entrepreneurship, we need more promoters who are interested in mining this wealth of talent to create new kinds of “special events” that can survive financially without relying on superstars. After all, there are lots of art lovers who want to go beyond Top 40 and its equivalents; the challenge is simply finding the stuff they like amid the avalanche of choice available today. So encouraging budding presenters is part of the solution.

But that’s not enough. We also need ways to support the van Goghs of today, the great artists who will be remembered through history but may never be appreciated in their lifetimes. For this, we need forms of artistic support that are not market driven, akin to the support models for basic research in science (though ideally divorced from the dysfunctions of the 20th-century academic music system). Historically, “basic research” support in the arts has come from visionary empresarios, but I’m not convinced that, on a societal level, relying on the generosity of wealthy art lovers is the most efficient solution. Part of the reason Social Security had the political support to become law is because private philanthropy was doing such a terrible job of caring for the needs of retired Americans. Similarly, it’s doing a pretty bad job of supporting American artists today, and a government-funded solution is probably the only realistic model.

This is not likely to happen overnight given today’s political landscape, but as artists we’re fooling ourselves if we think we can make things better through entrepreneurship. Some of us will rise to the top of the winner-take-all system. Others will develop entrepreneurial ventures on the periphery of art, usually related to technology, and usually by making the winner-take-all curve even more vicious for the rest of us. A few will stumble upon the philanthropic support they need to survive. But many more will waste their potential on entrepreneurial pipedreams unless we can focus the conversation on approaches that actually work.