Choir Psallite Deo (Photo Credit)

How to set text to make your music more interesting

For the January installment of my SoundMakers residency, I want to write about setting words to music. The piece I wrote for SoundStreams posed some interesting text-setting challenges, given the fact that it’s in Old French and every word echoes for 5–10 seconds after being sung. Text setting is an area where composers often miss the point, so I’m going to look at some of the key considerations involved, and then I’ll describe how those play out in a piece like Longuement me sui tenus.

Too many composers treat text setting like part making: an obligatory chore you have to do when you’re working with singers, but not an integral part of the compositional process. That’s a huge lost opportunity.

Words are special, and people hear them differently from other elements in music. They need to be treated the same way you would treat rhythm or harmony or phrasing. Done right, text setting can infuse your music with complexity and meaning you wouldn’t have gotten from sound alone. (This is, after all, the only way to explain the appeal of most of Bob Dylan’s oeuvre.) Done wrong, text setting distracts from the piece, makes your singers look awkward, and covers up the interesting bits in the music.

Intelligibility: is it really that important?

I’m sure you’ve seen those lists of commonly misunderstood lyrics—Jimi Hendrix’s “‘Scuse me, while I kiss the sky” heard as “‘Scuse me, while I kiss this guy” is one of the most famous examples. So my first rule of text setting is, counterintuitively, that you can never guarantee that everyone will understand the words. The goal is not perfect communication, it is effective communication.

The traditional school of text setting tells you that comprehension is always Goal Number 1, but our everyday experience with music tells us otherwise. Some people listen intently to the words, others don’t really notice them. Some songs are better when you listen to the text (e.g. Tom Waits, “Tom Traubert’s Blues”), others actually get worse if you pay too much attention to what the lyricist wrote (e.g. Black Eyed Peas, “I Gotta Feeling”).

Nothing all that special about the music, but the lyrics are genius.

Go ahead and shake your bootie, just don’t listen too closely…

Consequently, I take a more relativistic approach to text setting. Sometimes you’ll want to put the music in service of the words, sometimes it’ll be the opposite—but you should decide consciously. Adding words is not like adding an oboe to your Pierrot ensemble: text fundamentally changes the nature of the experience and our relationship with the other musical materials—even though the way we listen to lyrics varies wildly from person to person.

All those caveats aside, however, this doesn’t mean you can just ignore text-setting considerations. You will still want to follow Text Setting 101 rules most of the time. In its most basic form, this means you line up the stresses in the words and clauses with the stresses in the music. Notice how Hendrix does it: “‘SCUSE me / / while i KISS the SKY.” Classic text setting: the important words are emphasized metrically on strong beats, there’s a pause where the punctuation falls, the vocal rhythm more or less matches the default speech rhythm, and the ensemble cuts out to let the words be heard clearly.

Yet despite doing everything by the book, people consistently hear this phrase wrong! Part of that is in the word choice: kiss this guy is a much more probable phrase than kiss the sky. But part of it is also the fact that words in music are not wholly about communicating literal meaning. There’s a give and take between the emotional or sensory aspects of music and the linguistic meaning of the text. That’s why important words and clauses tend to get repeated in music much more often than they would be in speech (notice how the Da Capo aria has this functionality built into the form).

Music to stress textual meaning

If you only ever set text in a traditional, word-stress manner, your music will be really boring. Great text setting teeters on the intersection between intelligibility, musical meaning, and textual meaning. It provides a function similar to musical consonance and dissonance, where the push and pull of opposing forces makes the development interesting.

Sometimes, for example, you’ll use musical elements to emphasize some deeper meaning that sits beneath the words. The text may or may not be easy to understand, but there will be something unusual about the setting that is chosen because of how it connects to the music, not because it parallels everyday speech.

One of my favourite examples of this is from Xiu Xiu’s 2014 album Angel Guts. The song “Cynthia’s Unisex” features a relentless, driving synthesizer drone, pumping out a steady stream of noisy 16th notes throughout. Most of Jamie Stewart’s singing on the track is floating and arrhythmic, contrasting to the driving rhythm beneath it. However, at several points in the song, he breaks into a long, frantic stream of no no no no no no no no no no no synchronized precisely with the synth drone and declaimed in an unnaturally rapid style. (He also does it once on yes.)

The effect is jarring. The first time I heard it, it sent shivers down my spine. If the goal were simply to sing the word no, that could have been done in countless other ways that preserve intelligibility and mirror natural speech. Yet he purposefully chose an awkward text setting that sounds forced. Why? Because it parallels the angular synth part, making us acutely aware of its pervasiveness. It’s like someone suddenly pouring a bucket of cold water over your head: you can’t help but reassess your relationship to what’s going on around you. Musically, it also meshes beautifully with the ethos of the song, tying into the deeper paranoid quality of the lyrics. It’s a masterful example of a musical device used to emphasize textual meaning.

Words to stress musical meaning

Sometimes, you’ll also want to use words in service of a musical concept, even if it means fudging the textual meaning a little. You’ll find tons of this in James Brown’s singing, peppered as it is with Hey!, Whoo!, Yeah!, Smokin’!, Hit me!, Git down! and endless other vocal placeholders. “Get Up/Sex Machine”, “Hot Pants”, “Cold Sweat”, “Papa Don’t Take No Mess”—all great songs but not exactly pinnacles of poetic achievement.

Much of musical melisma also falls into this category. I love the Dirty Projectors’ “Police Story”, a raw, delicate tale of police brutality sung with an almost baroque level of melisma. When David Longstreth sings “They put me away” at the end of each verse, he dwells on away, turning it into a long, flowing melisma that completely destroys the intelligibility of the word. We can guess the word from the context that precedes it, but if we jumped in right there without context, we would have no idea what word he was singing. That’s okay, because the point is not to make the word more clear, it’s to drive the musical form, to create a sense of release before the next section.

Great text setters are not afraid of burying the lyrics when it suits the musical moment. Not all vocal music is about words, after all. If that weren’t the case, reading books of lyrics would be as popular as listening to music. Shifting the function of your text back and forth between its literal meaning and the musical meaning behind it is a fantastic way to create richness and complexity. It also “dummyproofs” your piece, by making it appealing to both people who like to focus on lyrics and those who don’t.

Flirting with Old French

With that context in place, I’m ready to say a few words about Longuement. First of all, the piece is in Old French, which nobody speaks anymore, so intelligibility is kind of a moot point. However, I didn’t want it to sound like I was ignoring intelligibility either. If the setting is awkward, it’ll trip up the singers and make the piece cumbersome, even if nobody understands the words.

For the most part, therefore, I followed the Text Setting 101 rules outlined above. I highlighted words that are important to the meaning of the piece and set them by stress. However, I also paid careful attention to words that resemble their modern French equivalents, which gave me another level of linguistic push/pull to play with: words you can understand vs. words you can’t. In the same way that a North American might not understand all of what the actors are saying in a slang-filled British sitcom, Longuement lets the French-speaking brain puzzle over the juxtaposition of familiar and unfamiliar words.

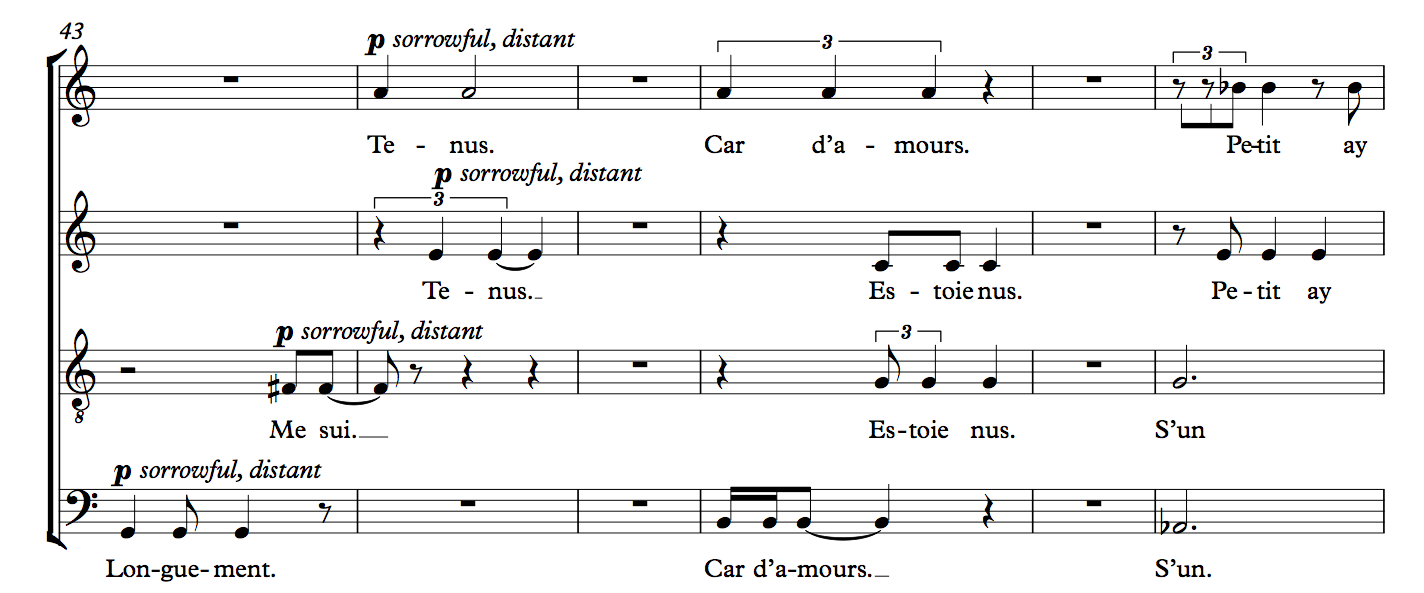

Example of tension between Old and Modern French words

In the example above, the Old French “Longuement me sui tenus” is not that different from the modern “Longuement je me suis retenu” (English: “For a long time, I’ve held myself back”). The missing je and the simple past tense might throw off modern French speakers, but it’s decipherable. The use of tenus instead of retenu is weird, since tenu(s) in modern French is the past participle of to hold [in your hands], not to hold back. You can sort of feel what it means, but there’s something off about it, and that creates a type of dissonance.

Similarly, “Car d’amours estoie nus” (“For of love I was bare”) flirts between sense and incomprehensibility. Car d’amours is straightforward in modern French, if a bit poetic, and nus matches the modern nu, meaning naked. You wouldn’t say, “I was naked of love” in modern French or in English, but the sense of lacking is there, leading your thought process in the same direction as the English words bereft or bare. What trips you up, though, is the verb form estoie, which sounds very different from the modern French j’étais. If you speak Spanish, you might see the connection with the verb estar, but it’s not obvious from a French perspective. So you’re left to guess blindly at the key verb in the sentence, again providing a tantalizing puzzle for the brain.

Sometimes it’s just music

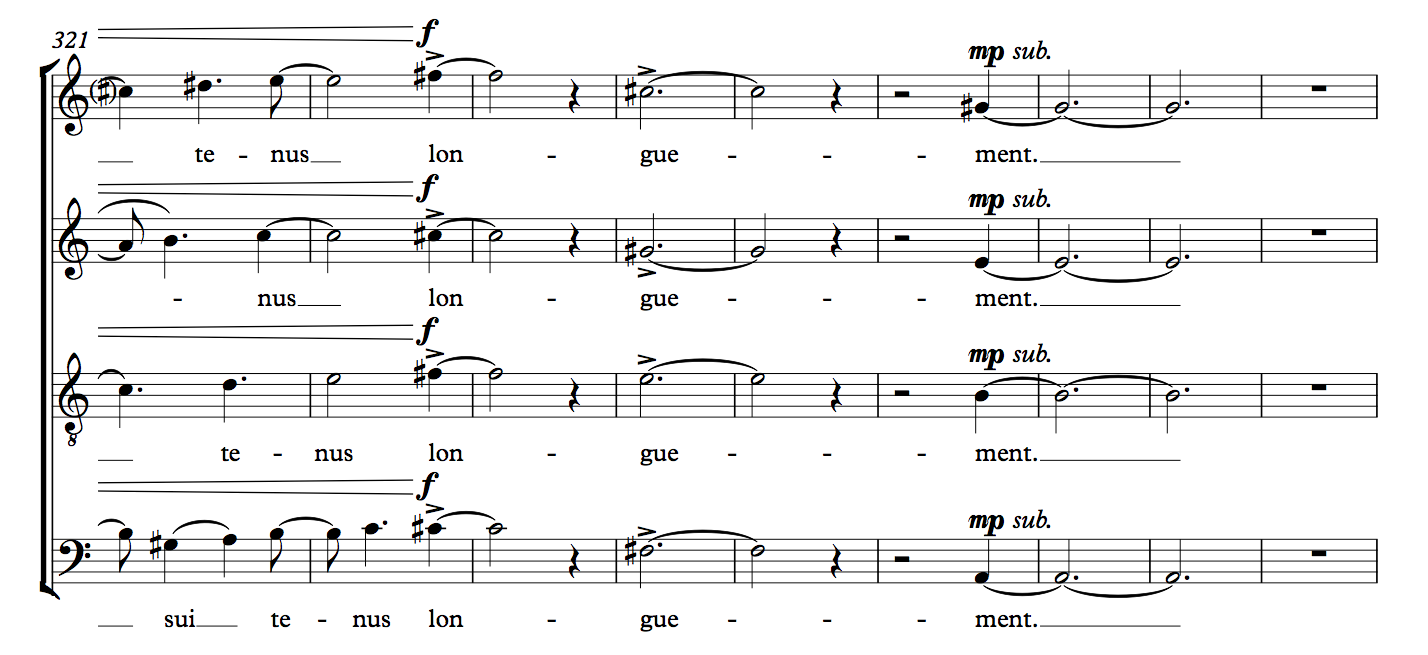

There were also times where I left the musical meaning override the textual meaning. As an overarching rule, music has to come first in this piece, since most people won’t understand the text. For the most part, the compromises between text and music worked themselves out elegantly, but one spot where I had to make a definite call was the forte climax described in my last post, shown again below.

The /o/ in longuement is impossible to sing accurately in this register

The section preceding this passage builds up a series of cacophonous runs that all end on the key word longuement. Each time, longuement gets a little bit longer, until we reach the climax and it’s stretched out over the forte high notes in each voice shown above. The problem, however, is that the vowel /o/ doesn’t work well that high and loud, because of the anatomy of the mouth. When sung, the passage above will give more of an open /a/ sound.

After some mulling, I decided the musical effect was more important to preserve. The shape of the line and the feeling of the climax trumps the need to understand the word. Besides, by this point in the piece, we will have heard longuement many times, and the entire preceding passage is based on it. So despite the word being mispronounced, there’s a good chance people will hear the intended text. Sometimes, it’s okay to break the rules, as long as you know why you’re doing it.

This post originally appeared on the SoundMakers composer-in-residence blog.