This is why your audience building fails

How do we increase the audience for new music? This is a never-ending debate, but virtually all of the standard answers assume that we need to be more inclusive, breaking down barriers for newcomers. From “people should be allowed to clap between movements” to “our next concert celebrates the work of composers from Latin America,” the common thread is evangelical: if we make the culture of new music welcoming to a broader range of people, new audiences will be won over by the universal artistic truth of our music.

This attitude is more or less unique to new music. Sure, every struggling indie band wants to play to larger houses, but the default boundaries of the audience are predefined, usually along class or ethnic lines. Country music has never seriously attempted to break into the African-American market (despite some important black roots). Norteño music does not worry about its lack of Asian American artists. Arcade Fire has probably never tried to partner with the AARP. Even Christian rock, which is fundamentally about evangelism, flips the relationship around: music to spread belief, versus belief to spread music.

So why do we put inclusivity at the center of our audience building? I suspect it is largely a reaction to our upper-class heritage: after all, our genre wouldn’t exist without the 19th-century bourgeoisie and 20th-century academia. Through openness, we hope to convince people that we’re really not that stuffy, that our music can have a meaningful place in people’s lives even if they aren’t conservatory-trained musicians or white upper-middle-class professionals.

Working toward greater diversity in new music is necessary and right. The problem is that we’re putting the cart before the horse. Greater inclusivity isn’t an audience-building strategy—it’s an audience-building outcome. Making inclusivity the focus of strategy actually hurts our efforts. All we do is muddle classical music exceptionalism with easily disproven assumptions about musical taste, in the process blinkering ourselves to certain truths about how people use music in pretty much any other context.

And what do we get for our efforts? The same small audiences of mostly white, highly educated music connoisseurs. If we truly want to cultivate both meaningful growth and meaningful diversity in new music audiences, we need to take a step back and examine how people choose the music they listen to.

Communities and Outsiders

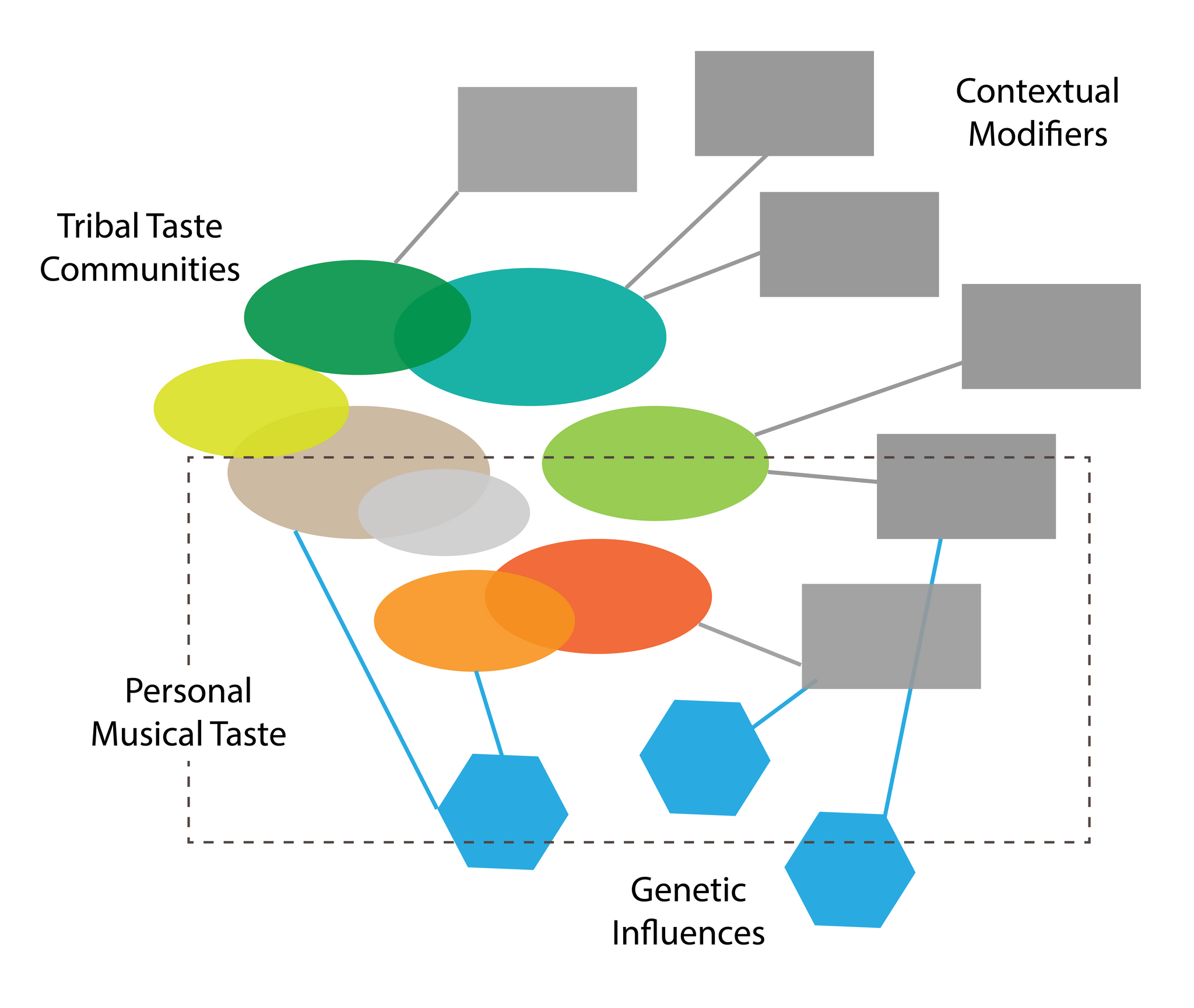

For the vast majority of people, music is—whether for better or worse—strongly connected to tribalism. It’s sometimes hard for us to see this as musicians because we treat sounds and genres the way a chef explores varietals and cuisines, each with unique properties that can be appreciated on their own merits.

Yet very few non-musicians relate to music in this way. Usually, musical taste is intertwined with how the listener sees him- or herself in the world. People choose their music the same way they choose their favorite sports teams or their political affiliations: as a reflection of who they want to be, the beliefs they hold, where they feel they belong, and the people they associate with.

In other words, musical taste is about community building—an inclusive activity. But whenever you build a community, you also implicitly decide who isn’t welcome. Those boundaries are actually the thing that defines the community. We see this clearly in variations in average tastes along racial or ethnic lines, but it’s just as important elsewhere: comparing grey-haired orchestra donors to bluegrass festival attendees, or teenagers to their parents, for example.

For most musical genres, it is the exclusivity of the community that is the selling point. Early punk musicians weren’t trying to welcome pop music fans—they actively ridiculed them. Similarly, nobody involved in the ‘90s rave scene would have suggested toning down the bold fashion choices, drug culture, and extreme event durations in order to make the genre more accessible.

Or consider the R&B family of genres: soul, funk, Motown, hip-hop, old-school, contemporary, etcetera. These are the most popular genres in the African-American community, at least partially because these genres are theirs. They made this music, for themselves, to address the unique experiences of being black in America. Sure, other people can (and do) enjoy it, make it, and transform it to their purposes. But only because everyone acknowledges that this is fundamentally black music. When Keny Arkana raps about the struggles of the poor in Marseilles, we don’t hear the legacy of Édith Piaf or Georges Brassens or modern French pop stars. We don’t hear the Argentine roots of her parents or other South American musical traditions. What we hear is an African-American genre performed in French translation.

The video for Keny Arkana’s “La Rage,” clearly influenced by African-American music videos.

In contrast, when genres get co-opted, like rock ‘n’ roll was, like EDM was, they lose their original communities. When we hear Skrillex, we think white college kids, bro-y sales reps, or mainstream festivals like Coachella—not the queer and black house DJs from Chicago and Detroit who pioneered EDM. Similarly, when we hear Nirvana or the Grateful Dead, we don’t hear the legacy of Chuck Berry or Little Richard. As exclusivity disappears, the music ceases to be a signifier for the original group, and that group moves on to something else. Community trumps genre every time.

Expanding the Circle

Things aren’t completely that clear cut, of course. There are black opera singers, white rappers, farmers who hate country music, grandmothers who like (and perform) death metal, and suburban American teenagers who would rather listen to Alcione than Taylor Swift. In addition, a lot of people like many kinds of music, or prefer specific music in certain contexts. We thus need a portrait of musical taste that goes beyond the neolithic sense of tribalism.

The first point to note is that communities of taste, like other communities, are not mutually exclusive. There are friends you would go to the gym with, friends you’d invite over for dinner, work friends you only see at the office, and so on. Some of these groups might overlap, but they don’t need to.

Similarly with music, there is music you’d listen to in the car, music you’d make an effort to see live, dinner music, workout music, wedding music, and millions of other combinations. Again, sometimes the music for one context overlaps with another, but it doesn’t necessarily need to. As such, while people make musical taste decisions based on tribe, we all belong to many overlapping tribes, some of which use different music depending on the context.

Film is one of the clearest examples of this contextual taste at work. Why is it, for instance, that most people don’t bat an eyelash when film scores use dissonant, contemporary sounds? Because for many people, their predominant association with orchestral music is film. As I’ve written before, when uninitiated audiences describe new music with comments like “it sounds like a horror movie,” they’re not wrong: for many, that’s the only place they’ve heard these sounds. Film is where this type of music has a place in their lives, and they hear atonality as an “appropriate” musical vocabulary for the context.

In addition, film gives us—by design—a bird’s-eye view into other communities, both real and imaginary. It’s a fundamentally voyeuristic, out-of-tribe medium. We as an audience expect what we hear to be coherent with the characters on the screen or the story being told, not necessarily with our own tribal affiliations. Sure, we definitely have communities of taste when it comes to choosing which films and TV shows we watch. But once we’re watching something, we suspend our musical tastes for the sake of the narrative.

Thus, when the scenario is “generic background music,” film offers something in line with our broad societal expectations of what is appropriate for the moment—usually orchestral tropes or synthy minimalism. However, when the music is part of the story, or part of a character’s development, or otherwise meant to be a foreground element, there’s a bewildering variety of choices. From Bernard Herrmann’s memorable Hitchcock scores, to Seu Jorge’s Brazilian-inspired David Bowie covers in The Life Aquatic, to Raphael Saadiq’s “all West Coast” R&B scoring of HBO’s Insecure—anything is possible as long as it makes sense for the taste-world of the narrative.

Dealing with Outliers

Lots of people have tastes that deviate from societal norms and tribal defaults, including (obviously) most of us in new music.

All that aside, we still need to explain the outliers: the death metal grandma, the young American Brazilophile, the black opera singer… Lots of people have tastes that deviate from societal norms and tribal defaults, including (obviously) most of us in new music.

In a case like the suburban teenager, it might be as simple as curiosity and the thrill of exoticism. But when we turn to examples like the black opera singer, things get more complicated. Making a career in European classical music is incredibly hard, no matter where your ancestors come from. But black people in America also face structural challenges like systemic racism and the high cost of a good classical music education in a country where the average black family has only one-thirteenth the net worth of the average white family. Making a career in music is never easy, and it doesn’t get any easier when you try to do it outside of your tribe’s genre defaults. Yet despite the challenges, there are clearly many black musicians who have persevered and made careers for themselves in classical music. Why did they choose this path through music?

The standard explanation leans on exceptionalism: classical music is a special, universal art form that has transcended racial lines to become a shared heritage of humanity, so of course it will be attractive to black people, too. That doesn’t really stand up to scrutiny, though. Rock ‘n’ roll is at least as universal. If it weren’t, Elvis Presley wouldn’t have been able to appropriate and popularize it among white Americans, and rock-based American pop wouldn’t have inspired localized versions in basically every other country in the world.

Jazz also has a stronger claim at universalism than classical music. Multiracial from its beginnings, incorporating both black and white music and musicians, then gradually broadening its reach to meaningfully include Latin American traditions and the 20th-century avant-garde—if there is any musical tradition that can claim to have transcended tribal barriers, it is jazz, not classical music. No, musical exceptionalism is not the answer.

Maybe this is an affirmative action success story then? I doubt that’s the whole explanation. Black Americans have been involved in classical music at least since the birth of the nation—a time when slavery was legal, diversity was considered detrimental to society, and polite society thought freedmen, poor rural hillbillies, and “clay eaters” were a sub-human caste of waste people not capable of culture. That environment makes for some strong barriers to overcome, and to what benefit? It would be one thing if there were no alternatives, but there have always been deep, rich African-American musical traditions—arguably deeper and richer than those of white Americans, who mostly copied Europeans until recent decades (after which they copied black Americans instead).

I asked a handful of black classical musicians for their perspectives, and their answers shed some light. Their paths through music varied, but everyone had mentors who encouraged their passion for classical music at key stages, whether a family member, a private instructor, a school teacher, or someone else. In addition, they all got deeply involved in classical music at a young age, before they had the maturity and self-awareness to fully comprehend how racism might play a role in their careers. By the time they were cognizant of these challenges, classical music was already a big part of who they were. They felt compelled to find their place within it.

W. Kamau Bell recently shared a similar story about his path into comedy in this Atlantic video.

These anecdotes provide a partial answer, but we still don’t know where the initial inspiration comes from, that generative spark that leads to an interest in a specific instrument or type of music. For example, cellist Seth Parker Woods tells me that he picked the cello because he saw it in a movie when he was five. Something about the cello and the music it made struck him powerfully enough that a couple of years later, when everyone was picking their instrument at school (he attended an arts-focused school in Houston), he thought of the movie and went straight to the cello. To this day, he remembers the film and the specific scene that inspired him. I was similarly drawn to percussion at a young age, begging my parents for a drumset, acquiescing to their bargain that “you have to do three years of piano lessons first,” and then demanding my drums as soon as I got home from the last lesson of the third year.

Nature or Nurture

There is something fundamental within certain people that leads us to specific instruments or types of music. And thanks to science, we now know pretty conclusively that part of the reason for this is genetic, although we don’t yet know a whole lot about the mechanics involved.

Now, before we go further, let’s be very clear about what genetics doesn’t do. It doesn’t preordain us biologically to become musicians, and it doesn’t say anything about differences in musical preference or ability between genders or ethnic groups. Simplistic mischaracterizations of that sort have been responsible for lots of evil in the world, and I don’t want to add to that ignominious tradition. What genetics does do, however, is provide a plausible theory for some of the musical outliers. It’s that extra nudge in what is otherwise a predominantly cultural story.

A major contributor to our understanding of music genetics is the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart. Started in the late 1970s and still going today, it has tracked thousands of sets of twins who were separated at birth and raised without knowledge of each other. The goal of the study and similar ongoing efforts is to identify factors that are likely to have a genetic component. Since identical twins have identical genomes, we can rule out non-genetic factors by looking at twins who have been raised in completely different social and environmental situations.

Most twin-study findings relate to physical traits and susceptibility to disease, but the list of personality traits with a genetic component is truly jaw-dropping: the kinds of music a person finds inspiring, how likely someone is to be religious, whether s/he leans conservative or liberal, even what names a person prefers for their children and pets.

And we’re not talking about, “Oh hey, these two boomers both like classic rock, must be genetics!” No, the degree of specificity is down to the level of separated twins having the same obscure favorite songs, or the same favorite symphonies and same favorite movements within those. In the case of naming, there are multiple instances of separated twins giving their kids or pets the same exact names. Moreover, it’s not just one twin pair here and there, the occurrence of these personality overlaps is frequent enough to be statistically significant. (For more in-depth reading, I recommend Siddhartha Mukherjee’s fascinating history of genetic research.)

It would seem that our genome has a fairly powerful influence on our musical tastes. That said, the key word here is influence—scientists talk about penetrance and probability in genetics. It’s unlikely that composers have a specific gene that encodes for enjoying angular, atonal melodies. However, some combination of genes makes us more or less likely to be attracted to certain types of musical experiences, to a greater or lesser degree. That combination can act as a thumb on the scale, either reinforcing or undermining the stimuli we get from the world around us and the pressures of tribal selection.

The genetics of sexual orientation and gender identity are much better understood than those of musical taste, and we can use those to deduce what is likely going on with our musical outliers. Researchers have now definitively located gene combinations that control for sexual orientation and gender, measured their correlation in human populations, and used those insights to create gay and trans mice in the lab, on demand. In other words, science has conclusively put to rest the nonsense that LGBTQ individuals somehow “choose” to be the way they are. Variations in sexual orientation and gender identity are normal, natural, and a fundamental part of the mammalian genome, just like variations in hair color and body shape.

When it comes to homosexuality in men, the expression of a single gene called Xq28 plays the determining role in many (though not all) cases. When it comes to being trans, however, there is no single gene that dominates. Rather, a wide range of genes that control many traits can, in concert, create a spectrum of trans or nonbinary gender identities. This makes for a blurry continuum that might potentially explain everything from otherwise-cis tomboys and girly men to completely non-gender-conforming individuals and all others in between.

When it comes to the genetics of musical taste, we’re likely to be facing something similar to the trans situation, in that individuals are predisposed both toward a stronger or weaker passion for music and a more or less specific sense of what kind of musical sounds they crave. All professional musicians clearly have a greater than average predisposition for music, since nobody becomes a composer or bassoonist because they think it’s an easy way to earn a living. Likewise, certain people will be drawn strongly enough to specific sounds that they’re willing to look outside of their tribal defaults, both as listeners and performers.

Let’s reiterate, however, that genetics plays second fiddle. One hundred years ago, classical music enjoyed a much broader base of support than it does today, which suggests that tribalism is the bigger motivating factor by far. If things were otherwise, after all, musical tastes would be largely unchanging over the centuries, and I wouldn’t need to write this article.

A theory of musical taste

Mason Bates’s Mercury Soul

Enough with the theorizing. Let’s turn to two specific new music events that make sense when viewed through a tribalist lens. Both are events that I attended here in San Francisco over the past year or so, and both were explicitly designed to draw new crowds to new music.

Mason Bates’s Mercury Soul series is at one end of the spectrum. Taking place at San Francisco nightclubs, the Mercury Soul format is an evening of DJ sets interspersed with live performance by classical and new music ensembles, all curated by Mason. These types of crossover concerts were instrumental to his early career successes and led to a number of commissions, many with a similar genre fusion twist. He is now one of the most performed living American composers.

A promo video for Mercury Soul.

When Mason’s work comes up in conversation, there is often reference to blending genres, breaking down barriers, and building audiences for new music. Yet Mercury Soul is a textbook example of the evangelical trope: bringing classical music into the nightclub with the assumption that clubbers will be won over by the inherent artistic truth of our music. Given the arguments presented above, you can see that I might be skeptical.

Let’s start with even just getting into the venue. As I was paying for admission, I witnessed a group of 20-somethings in clubbing apparel peer in with confused looks. Once the bouncer explained what was happening, they left abruptly. People come to nightclubs to dance, so when these clubbers saw that the context of the nightclub was going to be taken over by some kind of classical music thing, their reaction was, “Let’s go somewhere else.” Maybe they thought the concept was weird or off-putting. Or maybe they didn’t really get it. Or maybe they thought it was a cool idea but they just wanted to go dancing that night. It doesn’t really matter, because if you can’t get them in the door, you’re not building audiences.

Wandering into the venue, I saw something I’ve never seen at a nightclub before: multiple groups of grey-haired seniors milling around. Of the younger crowd, many were people I know from the Bay Area new music scene. There were obviously attendees who were there because they were regulars, but more than half the room of what looked like 200-300 people were clearly there either for Mason or one of the ensembles who were playing.

The evening unfolded as a kind of call and response between Mason’s DJing and performances by the ensembles, often amplified. During the live music segments, people stood and watched. During the electronic music segments, they mostly did the same. People did dance, but the floor remained tame by clubbing standards, and the lengthy transitional sections between DJing and instrumentalists gave the evening a feeling of always waiting for the next thing to happen. The DJ portion lacked the non-stop, trance-inducing relentlessness that I loved back in my youthful clubbing days, yet the live music portion felt small in comparison—and low-fidelity, as it was coming through house speakers designed for recorded music. As is often the case with fusion, both experiences were diluted for the sake of putting them together. The end result didn’t feel like audiences coming together, it felt more like classical music colonizing another genre’s space.

That was my experience, but maybe it was just me? I attempted to interview Mason to get his take on the impact of Mercury Soul, but we weren’t able to coordinate schedules. However, in speaking to people who have been involved as performers, what I experienced was typical. Mercury Soul has gotten some positive buzz from the classical music press, but reactions from the non-classical press have been tepid at best, and interest in the project remains firmly rooted within traditional new music circles.

To be fair, this doesn’t imply that the concept is doomed to failure. I could certainly see Mercury Soul evolving into a unique musical experience that has appeal beyond the simple act of genre fusion. As I’ve argued above, communities of musical taste are not particularly concerned with what the actual music is, so why couldn’t a community develop around genre mashups in a nightclub?

In other words, the music is not Mercury Soul’s problem. Rather, the problem is that Mercury Soul hasn’t tried to foster a community. Instead, it makes all the standard assumptions about audience building, which means that, best case scenario, members of the taste communities being thrown together might perceive the experience as an odd curiosity worth checking out once or twice. In the end, therefore, Mercury Soul’s true community is neither clubbers nor new music aficionados—it’s arts administrators and philanthropists desperate to attract younger audiences.

SoundBox

In contrast, let’s look at the San Francisco Symphony’s (SFS) SoundBox series. These events take place in one of the rehearsal rooms at Davies Symphony Hall, which is converted into a sort of warehouse party space, with multiple elevated stages, video projection screens, lounge-style seating, and a bar. The entrance is from a small rehearsal door on the back side of the building, and the room is not used for any other public performances, so everyone who is there has to come specifically for SoundBox. Initially, SFS also made a conscious decision to omit its brand entirely from the events, so most attendees were not aware of the SFS connection before they arrived.

Each program is curated by a prominent musician, many composers among them, and the repertoire is almost entirely new music, performed acoustically (or with live electronics) from a stage, as it normally would be, and accompanied by custom video projections. The performers are drawn from the SFS roster, and they present multiple short sets throughout the evening. During the sets, people sit or stand quietly and listen to the music. The rest of the time, they mill about, chat, and get drinks from the bar. When I went, there were about a dozen or two of my colleagues from the new music scene present, but the rest were people I didn’t recognize, most of them in their 20s and 30s.

In terms of reception, SoundBox could not be more successful. There are two performances of each show, with a maximum capacity of 400 people per evening. I spoke with a friend who works for the Symphony, and he told me that SoundBox always sells out—in one case, within 20 minutes of the tickets going on sale. And this with no marketing budget: low-cost online promotions and word of mouth are the only way they promote the events. Two thirds of SoundBox attendees are new each time, the vast majority are under 40, and very few are SFS subscribers.

Contrast the messaging of SoundBox’s promo video to that of Mercury Soul.

Unlike Mercury Soul, SoundBox starts out by defining a community: it’s a place for culturally inclined music lovers to discover new, stimulating experiences. SoundBox then presents its music as a sort of rare gem worth expending a bit of effort to unravel, in the same way a winery might offer guided tastings of rare vintages. As a result, the event ends up feeling exclusive and mysterious, as if you are part of an elite group of in-the-know art connoisseurs. Whereas so many new music events give off the desperate air of trying too hard to be cool—“Look, we perform in jeans! We don’t mind if you clap between movements!”—SoundBox doesn’t have to try. It just is cool, appealing to the same type of confident cosmopolitanism that has allowed modern art museums to draw enthusiastic crowds far in excess of most new music events.

Despite its successes in building new music audiences, however, SoundBox has failed to meet SFS’s objectives—ironically, for the same reasons as Mercury Soul. The Symphony wants SoundBox to be a sort of gateway drug, encouraging a younger crowd to attend its regular programming. Yet despite an aggressive push to market to SoundBox attendees, my contact tells me there has been virtually zero crossover from SoundBox to SFS’s other programs. To further complicate things, SoundBox is a big money loser. An audience of 800 people paying $45/ticket and buying drinks seems like a new music dream, but it doesn’t pencil out against the Symphony’s union labor commitments, which were negotiated with a much bigger orchestral venue in mind.

This is not a failure on a musical level, but it is a failure in SFS’s understanding of audience building. SoundBox met a strong and untapped demand for a sophisticated, unconventional musical experience, and it created a community of musical taste around it, quite by accident. But it’s a different community from that of the orchestral subscriber, focused on different repertoire, different people, and a different experience. The fact that it is presented by SFS is inconsequential.

To recap, then, Mercury Soul fails to encourage 20-something clubbers to seek out new music because it doesn’t create a community of taste. On the other hand, SoundBox does create a community of taste, but it’s one that is interested in coming to hear Ashley Fure or Meredith Monk in a warehouse space. More importantly, it’s a community that has no preconceptions about how this music is supposed to fit into their lives, which allows them to deal with it on its own terms. With that context in mind, it’s more than a bit ridiculous to assume that those same people will be automagically attracted to a Wednesday night concert subscription of Brahms, Beethoven, and Mozart. That is a music most SoundBox attendees associate with their grandparent’s generation, performed in a venue that has strong pre-existing associations that don’t help.

Lessons Learned

We live at a time that is not especially attuned to musical creativity. All the energy spent on audience building is a reaction to that. I have a couple of friends who are professional chefs, working in our era of widespread interest in culinary innovation. When I ask them about the SF restaurant scene, they complain that too many chefs chase fame, recognition, and Michelin stars instead of developing a unique artistic voice.

As a composer, I only wish we had that problem. Yet the situation was reversed in the mid-20th century, when works like Ligeti’s Poème symphonique could get reviews in Time Magazine but culinary culture was being taken over by TV dinners, fast food, artificial flavoring, processed ingredients, and industrialized agriculture.

Whatever the reasons for the subsequent shift, our task is to find ways to bring musical creativity back to the mainstream. Looking at the problem through the lens of communities of taste offers some insights into what we might do better:

Community Before Music

People will always prioritize their taste communities ahead of your artistic innovation. That means you either need to work within an existing community, or you need to fill a need for a new community that people have been craving.

The first solution is how innovation happens in most pop genres: musicians build careers on more mainstream tastes, and some of the more successful among them eventually push the artistic envelope.

With new music, this doesn’t really work. On the one hand, the classical canon is not an ever-changing collection of new hit songs but rather an ossified catalog of standard works. On the other, the more premiere-focused world of new music is a small community—that’s the problem to begin with.

So we are left with finding untapped needs and creating new communities around them. SoundBox proves that this is possible. It’s up to us to be creative enough to uncover the solutions that work in other contexts.

Forget Universalism

Despite my critiques of classical music exceptionalism, there are good reasons why new music should endeavor to become a truly post-tribal, universal genre. Those reasons have little to do with the music itself and everything to do with the people making it.

One of the distinguishing characteristics of new music is that we attract an extremely diverse range of practitioners who are interested in synthesizing the world’s musical creativity and pushing its boundaries. What better context in which to develop a music that can engage people on an intertribal level?

That said, this is not our audience-building strategy, it’s the outcome. The way we get to universalism is to create exclusive taste communities that gradually change people’s relationships with sound. First we get them excited about the community, then we guide the community toward deeper listening.

This is similar to what is known about how to reduce racial bias in individuals. Tactics like shaming racists or extolling the virtues of diversity don’t work and can even further entrench racist attitudes in some cases. However, social science research shows that a racist’s heart can be changed on the long-term by having a meaningful, one-on-one conversation with a minority about that person’s individual experiences of racism. By the same token, to get to an inclusive, universal new music, first we need to get people to connect with our music on the personal level through exclusive taste communities that they feel a kinship with.

The MAYA Principle

Problems similar to new music’s lack of audience have been solved in the past. Famed 20th-century industrial designer Raymond Loewy provides a potential way forward through his concept of MAYA: “most advanced yet acceptable”. Loewy became famous for radically transforming the look of American industrial design, yet he was successful not just because he had good ideas, but rather because he knew how to get people warmed up to them.

One of the most famous examples is how he changed the look of trains. The locomotives of the 19th-century were not very aerodynamic, and they needed to be updated to keep up with technological advancements elsewhere in train design. In the 1930s, he began pitching ideas similar to the sleek train designs we know today, but these were very poorly received. People thought they looked too weird, and manufacturers weren’t willing to take a chance on them.

Therefore, he started creating hybrid models that resembled what people knew but with a couple of novel features added. These were successful, and he eventually transitioned back to his original concept, bit by bit, over a period of years. By that time, people had gotten used to the intermediary versions and were totally fine with his original. He repeated this process many times in his career and coined MAYA to describe it.

What I like most about MAYA is that the last letter stands for acceptable, not accessible. I think the accessibility movement in classical music has been one of the biggest arts marketing disasters of all time. It gives nobody what they want, dilutes the value of what we offer, and associates our music with unpleasant experiences.

Loewy got it right with acceptable. He was willing to challenge his audiences, but he realized that they needed some guidance to grapple with the concepts he was presenting. We in new music similarly need to provide guidance. That doesn’t mean we dumb down the art, it means we help people understand it, in manageable doses, while gradually bringing them deeper.

Hard is not Bad

Often in new music we are afraid to ask our audiences to push themselves. That’s a mistake. People like meaningful experiences that they have to work for. The trick is convincing them to expend the effort in the first place.

To get there, we start with the advice above: build communities, then guide people into greater depth using MAYA techniques. Miles Davis’s career illustrates this process beautifully. He didn’t start out playing hour-long, freeform trumpet solos through a wah-wah pedal; he started out identifying the need for a taste community that wasn’t bebop and wasn’t the schlocky commercialism of the big band scene. This led him toward cool jazz, where he developed a musical voice that propelled him to stardom.

After Miles had won over his community, however, he didn’t stop exploring. He expected the audience to grow along with him, and many of them did. Sure, plenty of jazz fans were critical of Miles’s forays into fusion and atonality, but he was still pulling enough of a crowd to book stadium shows. There’s no reason new music can’t do the same, but we have to be unapologetic about the artistic value of our music and demand that audiences rise to meet it.

Define Boundaries

Since new music is trying to build audiences that transcend racial and class boundaries, we need to be super clear about who we’re making music for and who we aren’t. “This music is for everybody” is not a real answer. We must explicitly exclude groups of people in order to be successful community-makers. It is my sincere hope, however, that we can find ways to be effectively exclusive without resorting to toxic historical divisions along racial and class lines.

Here’s one potential example, among many, of how that could work. I’ve argued before that the “eat your vegetables” approach to programming is dumb. There is rarely any good reason to sandwich an orchestral premiere between a Mozart symphony and a Tchaikovsky concerto. Conservative classical audiences don’t gradually come to love these new works, they just get annoyed at being tricked into sitting through a “weird” contemporary piece. New music audiences for their part are forced to sit through standard rep that they may not be particularly passionate about. Nor does this schizophrenic setup help build any new audiences—you have to be invested on one side or the other for the experience to make any sense to begin with.

So instead of trying to lump all this music together, a new music presenter might decide that audiences for common practice period music are fundamentally not the same as those drawn to Stockhausen or Glass or premieres by local composers. Armed with that definition, the presenter might then choose to create an event that would be repulsive to most orchestra subscribers but appealing to someone else, using that point of exclusion as a selling point. Thus, an exclusive community of taste is created, but without appealing to racism or other corrosive base impulses.

To close, I want to say a brief word about my motivations for writing this piece. Even though this is a fairly lengthy article, I’ve obviously only scratched the surface. The writing process was also lengthy and convoluted, dealing as we are with such a broad and opaque issue, and at many points I wondered if it was even possible to say something meaningful without a book-length narrative. Yet I feel that this subject is something we collectively need to wrap our heads around.

Big-picture questions like how people develop musical taste tend to get glossed over because they are so nebulous. But that doesn’t mean they’re unimportant. As musicians and presenters, we make decisions based on theories of musical taste every day, whether or not we articulate our beliefs. Taste is, in a sense, the musical equivalent of macroeconomics: hard to pin down, but the foundation of everything else we do.

My hope with this piece is that we can start talking about these issues more openly, drop some of the empty rhetoric, and stop spinning our wheels on the dysfunctional approaches of the last 40 or 50 years. Paying lip service to inclusivity is not enough. If you’ve read this far, then chances are you believe like I do that new music offers the world something unique that is worth sharing as broadly as possible. We desperately need to get better at sharing it.

Note: This post originally appeared at NewMusicBox.