“Construction worker” by Christoph on on Flickr.

Fixing American Arts Philanthropy: 3. Fund Existing Needs, Not Make-Work Projects

A common complaint among grant recipients, both in the arts and more generally, is that too many funders only support “new capacity”: they aren’t willing to chip in towards general operating expenses or other core activities that require ongoing support. It’s not hard to see why this is. Overhead is not a particularly sexy thing to fund, it doesn’t produce flashy case studies to show off—and of course it’s much easier to fund one-off projects with finite bounds than ongoing programs that demand detailed auditing.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with project-based philanthropy when it’s one funding option among many, but it becomes problematic when it’s the only show in town. The imbalance fosters lopsided organizational growth. It encourages waste and misuse. It can even backfire financially, creating costs in excess of what recipients receive in funding. The Center for Effective Philanthropy maintains a publication called “Nonprofit Challenges” (PDF), drawing on surveys of grant recipients, and the overabundance of project-focused funding shows up as one of the most widespread concerns:

As one leader said, “Stop designing programming and opportunities for which capacity must be created. Start with what each of us has the capacity to do and help us grow… as opposed to ‘Don’t drop anything and add this if you want funding.’” Another said, “One of our biggest challenges is that funders often want to support something ‘new’ or a specific project. If the project is not fully funded, it actually ends up costing us money.”

I’m not suggesting all foundations drop project-based programs entirely. But more funders need to support core activities and general operating expenses if they want to foster an arts community with longevity, one where talented artists and innovative organizations are able to build upon past accomplishments instead of reinventing the wheel for each grant cycle. Capacity for core activities funding certainly increases with foundation size, so yes, the very smallest funders may not realistically be able to do much. But the vast majority can and should fit some type of core activities funding into the broader context of their grant making.

Creative accounting and educational outreach

To my mind, the strongest argument in favor of funding operating expenses or core activities is that it encourages quality. Artists and organizations who are being evaluated on the entire range of their activities have an incentive to prioritize excellence, to tackle their core missions as rigorously as possible. They must account for the entirety of their work, refine their approaches, and face their strengths and weaknesses honestly and objectively. If they don’t rise to this standard they don’t get funded, so core activities support generates a virtuous circle between funders and grantees.

On the other hand, an exclusive focus on new capacity encourages puffery and shortcuts. Applicants need to present a polished image of themselves, but they know it won’t be audited in any depth, so that image can be one-sided, tailored to the priorities of the funder. Instead of focusing on making their work as good as it can be, applicants are incentivized to make their projects match the funder’s priorities. That, in turn, creates pressure to dilute their core concerns for the sake of acquiring funding.

Of course artists rarely set out to do shoddy work on purpose. But shiny prizes are attractive, especially in a chronically underfunded area like that arts. It’s a slippery slope from “how can we fund this project that advances our mandate” to “our mandate is whatever we can get funded.” Very few nonprofit arts presenters, especially on the small-ensemble scale, have the force of will to stick to the high road indefinitely without some form of encouragement. Many are subsidizing their activities through teaching or other employment, even after years of working at it, so there is strong structural pressure to take shortcuts. Eventually, the allure of the sunk costs fallacy becomes overwhelming: with so much time and effort already invested, goal #1 becomes remuneration, at any cost.

An explanation of how the sunk costs fallacy works.

Consider the ubiquity of educational outreach programs. As a musical ensemble, there is certainly value in devoting part of your efforts towards education, but come on: does every string quartet in America really need its own outreach program? I’m willing to bet a good number of these ensembles were formed because they wanted to perform great string quartet repertoire, not because they wanted to give masterclasses in school gymnasiums. Yet they apply for educational funding nonetheless. There are a lot of educational grants, after all, and that money can be funneled toward overhead expenses if the organization does the outreach work on the cheap.

Wouldn’t it be better to fund educational initiatives whose top priority is quality arts education? That doesn’t mean educators shouldn’t collaborate with professional performing arts organizations, but you’ll probably get a better return on investment by supporting a masterclass program put on by a proven educator like the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts instead of throwing money at dozens of half-hearted, half-baked programs put on by performing ensembles.

Of course, there will be exceptions, and not all arts education grantees need to be large institutions. Some string quartets, regional orchestras, and other presenters do have something of value to add to the arts education landscape. But funders should figure out whether these ensembles are doing educational outreach for its own sake or simply because it’s an additional revenue stream. And that requires rolling up the proverbial sleeves and getting involved in core activities.

“Big Data” and leukemia research

Sidney Farber with a young patient. National Cancer Institute, AV Number: AV-6000-3214, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Too much focus on projects also distorts the perspective of funders, because it places a premium on short-term results and PowerPoint-friendly measures of success. We live in an age that glorifies quantification and quarterly returns, but that doesn’t mean all problems can be solved by data. Especially in the philanthropic sector, we find a preponderance of needs that don’t play nice with the metrics of the business world. After all, if this weren’t the case we wouldn’t need nonprofits—everything could be structured as a business.

When funders only look at one-off projects or new capacity, measuring takes on outsized importance. Lacking the big picture of an applicant’s activities, funders naturally need some other way to justify their choices. In the interests of transparency and perceived accountability, therefore, data collection gets called to bat—and the more data, the better.

Unfortunately, every method has its biases. By focusing too heavily on data collection, we have inadvertently created a philanthropic landscape that mirrors the “clear law” trend criticized by legal theorist Philip K. Howard: clear law, our society’s preference for ever-increasing bureaucratic detail in lawmaking, hasn’t lead to the reduction in error or improvement in governance efficiency we hoped it would. Instead, it has buried administrators in red tape and abdicated them of personal responsibility, creating a situation where nothing gets done and nobody is to blame. Similarly, in the quest for greater fairness and effectiveness, arts funders end up obsessing over data collection at the expense of useful results, losing track of the larger purpose and prioritizing projects of limited scope and questionable impact.

My wife and I had lunch recently with a friend who is a professional grant writer. As we placed slices of ham and homemade zucchini pickles on bread, the conversation turned to her recent work. She expressed frustration at an uptick in innovative organizations with solid track records being turned down because their programs don’t fit neatly within a quantitative framework. The funders had adopted a business-inspired attitude to performance metrics that placed unrealistic and counterproductive demands on applicants.

In one case, funders told a community dance program that they would need to provide quantitative evidence of improved participant health to receive funding. In another, they told a popular gardening program for abused children they would need to track participants’ BMI, quantify changes in their families’ eating habits, and collect information on their mental health—a herculean (and invasive) task that would have required parental consent forms, liaising with healthcare providers, and a major investment in HIPAA-compliant data collection infrastructure.

These applicants and the others she described are highly experienced, have a track record of success, and suggested relevant, realistic measures of success in their applications. Yet because their programs were fundamentally qualitative, they got turned down. Meanwhile, the programs that did get funded tended toward modest aspirations, limited impact—and the creation of impressive line graphs.

xkcd illustrating the danger of graphs

Data-driven studies have been immensely important to society, but we all know that some things can’t be meaningfully quantified—there is no correlation, after all, between number of Facebook friends and satisfaction with one’s social life. The problems that philanthropy aims to solve—especially in the arts—tend not to be the data-philic ones. They tend to be the ones where long, slow, nonlinear progress is the norm and measurement is difficult or counterproductive or both. We can certainly use evidence-based methods where they apply, but there are fundamental limits. Yet instead of designing grant programs around these limits, too many funders are instead limiting their applicants by forcing them to jump through meaningless quantitative hoops.

Consider the early days of chemotherapy research. After Sidney Farber discovered the first partially effective leukemia drug in the late 1940s, hopes were high that a cure for cancer was just around the corner. The Jimmy Fund was established in 1948 to bankroll construction of what is now called the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and money poured in from around the country. Yet despite initial successes and ample funding, things quickly plateaued. Permanent remission rates remained stubbornly low for decades, with nearly all leukemia patients eventually relapsing. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that serious progress was made in lowering the mortality rate, thanks to frustratingly exhaustive testing and a series of important “ah ha” moments that stemmed from it, changing the cancer research paradigm in productive ways. What would have happened if Farber and his successors had been held to the kind of quantification-fueled, project-based philanthropy we see today? His institute would never have been built, research funding would have dried out almost immediately, and leukemia would still be a death sentence.

Philanthropic institutions can’t afford to go down this path, propagating the mistakes of “clear law” and Big Data in their work. Funders rather need to focus on the uniqueness of their position, finding ways to make meaningful contributions that other types of institutions can’t. After all, philanthropy is not inherently valuable in and of itself; successes like the fight against leukemia are what make it worthwhile. And let’s remember, philanthropy didn’t always enjoy the stature it does today. In the early decades of the 20th century, charitable gifts by the Rockefellers, Carnegies, and Morgans of the world were treated with suspicion, because people assumed ulterior motives underlaid their generosity. If a foundation doesn’t fund core activities, and if the projects it does support are increasingly predicated on tangential or unrealistic measures of success—well, guess what: its relevance as a philanthropic organization will eventually come under fire.

Following the smart money

Conductor Michael Morgan with the Oakland East Bay Symphony

There’s also something to be learned by looking at how the smarter arts organizations navigate today’s project-heavy funding landscape. To my mind, the Oakland East Bay Symphony is a presenter that stands out from the pack on a programming and organizational level, and so I contacted Executive Director Steve Payne to see if he would share his perspectives with me. We met for burritos near the orchestra’s office in downtown Oakland and chatted about how the organization funds its activities.

First, a bit of background. The Oakland East Bay Symphony was formed out of the ashes of the former Oakland Symphony, a prestigious orchestra that had built a subscriber base as large as the San Francisco Symphony’s by the 1970s. Yet despite many accomplishments, the orchestra grew too big to be sustainable. It didn’t survive the arts cutbacks of the 1980s, shuttering operations in the midst of a labor dispute in 1986. Therefore, when the Oakland Symphony Orchestra League formed the newly minted Oakland East Bay Symphony in 1988, they knew the old approach wasn’t going to cut it. They took a hard look in the mirror and built a new organization predicated on the needs of its community and the funding available.

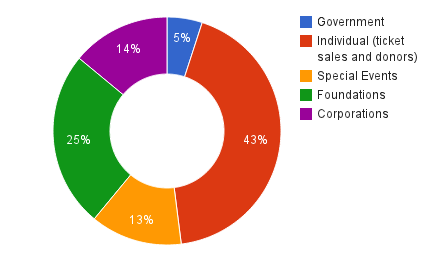

Payne has only been with the organization for a little over a year, but he was able to provide insight into their relationship with institutional funders as well as their overall strategies for fundraising. He described their funding mix as pretty typical, and I’ve included the chart he gave me below for reference.

As you can see, individuals are the largest slice of the pie. The orchestra has positive working relationships with a number of philanthropic foundations, but growth in that area is not Payne’s top fundraising priority. He sees more potential in the individual donor base. With the notable exception of the Hewlett Foundation (which he frequently praised as a leader in arts philanthropy), most foundations are only willing to fund one-off projects or new capacity. Yet the spectre of the Oakland Symphony collapse looms large: having been burned before, the organization isn’t willing to chase projects that will draw resources away from its core activities or stretch it beyond its means.

This would be a smart move for any arts organization, but it’s essential for a group like this one. After all, the Oakland East Bay Symphony exists in a competitive metropolitan region that has access to nearly a dozen professional orchestras, including the world-renowned San Francisco Symphony just a short subway ride from downtown Oakland. Good music played well isn’t enough: the symphony needs to foster a loyal community that is personally invested in the orchestra’s core mission.

From what I’ve seen, they have succeeded in doing this. The orchestra’s community, in fact, is what first attracted my attention. It’s obvious from the moment you enter the Paramount Theatre lobby that the people filing into their seats believe they’re part of something special. There is a palpable sense of enthusiasm, a general sense of good cheer, and a collective air of pride in the orchestra.

Diluting this loyalty by focusing on off-core projects would be extremely risky, no matter how lucrative the offer. Conversely, the enthusiasm of the organization’s supporters is contagious, so it makes sense to turn to this base for new funding opportunities. As such, Payne is investing in detailed donor research and analysis. He wants to better understand what makes someone take the leap from one-time supporter to ongoing patron, then build upon those factors to deepen the orchestra’s ties to the community.

That said, the Oakland East Bay Symphony doesn’t ignore arts foundations entirely, but they have a built-in incentive (unlike most arts organizations) to work with foundations productively. The orchestra maintains a running list of potential projects that would support its mandate but that aren’t essential to its concert season: guest artist programs, special events, collaborations with other organizations or venues, etcetera. They prepare detailed financial projections for each project and rank them in terms of their importance to the orchestra’s mandate. Then they wait. If enough stars align logistically or otherwise for a given project, the orchestra starts looking at potential funding channels, including all the applicable arts foundations. Project-focused philanthropy thus plays second fiddle most of the time, but it is called upon when the orchestra is, in fact, mounting a project.

Finding a path toward core activities funding

The Oakland East Bay Symphony is the exception to the rule. On the whole I’ve seen project-based philanthropy lead artists and arts organizations down the wrong path more often than not, even as it drives funders to focus on short-sighted or counterproductive measures of success. We desperately need a philanthropic landscape that includes more funding for general expenses and fewer make-work (or “make case study”) projects. For the individual artist, this means more programs like the MacArthur Fellowship or the Pulitzer Prize, though ideally not all targeted at the superstar artist. For arts organizations, it means more general expenses funding, in the vein of the Hewlett Foundation’s activities. Here are some suggestions for how we might get there:

Team up with other foundations – An easy solution would be to follow in Warren Buffett’s footsteps: he recently gave $2.1 billion to the Gates Foundation, basically leaving the problem to someone else. That’s obviously not practical (or desirable) for most foundations, but there is a middle road. Funders that can’t manage the administrative burden of funding core activities on their own could team up with others, then pool resources and expertise.

Prioritize long-term relationships – It’s easier for funders to understand the big picture when they work with grantees over the long term. Everyone wants to help as many applicants as possible, but there are disadvantages to biting off more than you can chew, as I’ve previously discussed. To my mind, it’s better to be the foundation that helps nurture a handful of well-known, world-changing arts organizations than the one that continually sprinkles its money across a bunch of little-noticed flops. This doesn’t mean, however, that funders need to place their bets and grit their teeth through thick and thin. Long-term granting programs could be designed on a conditional, open-ended framework: funders and grantees agree on mutually applicable goals and timelines, with funding provided periodically, then halfway through each funding cycle the program is reevaluated and decisions are made on revised goals, ongoing funding, and all the rest of it. When one of these relationships ends, the funder makes an open call for someone else to take the previous grantee’s place, or the funder approaches promising project-based grant recipients about entering into a more permanent arrangement.

Don’t follow the pack – Nationally, 55% of arts funding goes to 2% of arts organizations—everyone wants to back a winner. But following the pack increases the auditing burden for funders: well-funded organizations are more financially complex, less incentivized toward frugality, and less receptive to feedback. Smaller arts funders would do better to zero in on promising underdogs that follow a leaner operational model. This makes auditing easier, and the impact of funding becomes much more apparent since the scope of core activities is smaller.

Learn from the best – Funding core activities isn’t something you need to figure out from scratch—there are many foundations already doing it, and you can learn from their experiences. One of these is the Hewlett Foundation, mentioned above. They provide advice to other philanthropic organizations on how to improve operational efficiency in a number of areas, including strategies for general expenses funding. Another resource is the Center for Effective Philanthropy, whose primary asset is a large dataset of grant applicant survey responses across all areas of philanthropy. They use this information to benchmark the effectiveness of philanthropic organizations, comparing them to similar funders doing related work.

Previously in this series:

- Fixing American Arts Philanthropy: 1. Accept Fewer Applicants

- Fixing American Arts Philanthropy: 2. Don’t Sabotage Artistic Merit