Violinist busking, photo CC by meltsley on Flickr

Why Musicians Aren’t Paid More Fairly

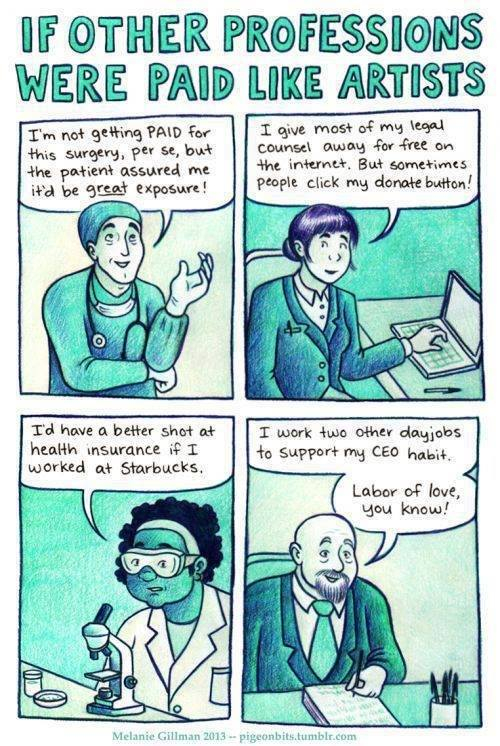

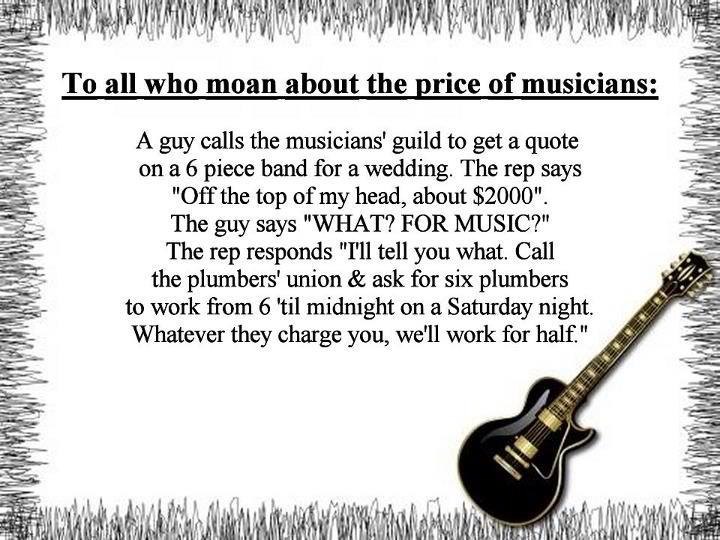

Periodically I see these memes on Facebook: “If surgeons were paid like musicians…,” or “Hire a plumber for the same service and we’ll play for half that.” I sympathize, but this is the wrong approach. Moral finger-wagging has never won any argument, ever, and if it were to work in music it would have decades ago. So how do we actually solve this problem of musicians’ lack of economic clout?

First, we need to understand what’s actually going on. The moralists cling to the delusion that it’s just a matter of education, but even musicians can’t decide what fair compensation is: I’ve had the exact same budget called “extravagant” by one jury panel and “overly ambitious” by another. And to throw salt on the wound, moralizing also hurts our collective bargaining power. Take the common story of the lowballing nightclub owner who gets chewed out by an indignant jobbing musician. The lecture doesn’t make the owner any less likely to lowball the next musician. In fact, it’s the opposite: you’ve just shown him that he has all the power in the relationship.

Apples and oranges in the walled garden

There’s a good reason musicians and surgeons aren’t paid the same way: the medical profession needs objective standards, but objective standards would hurt music. In 1827 when Beethoven was dying of lead poisoning, pretty much anyone with a little family inheritance could become a surgeon. Neither blood types nor the cause of infection had been discovered, so surgeons would carry freshly used scalpels in their pockets, going from patient to patient. Nobody washed their hands and wounds were not cleaned or bandaged. Until the discovery of ether in the 1840s, a stiff drink was the only anesthesia.

Understandably, surgeons didn’t have the best reputations, and people visited them only as a last resort. But science advanced, a corpus of medical knowledge evolved, and surgery grew into a modern profession. Doctors set up regulatory boards to stop overconfident quacks from butchering innocent people, and they began requiring more rigorous medical training prior to certification. The fact that you have to survive through more than a decade of soul-crushing course loads, endure inhumane 30-hour residency shifts, wear diapers to get through marathon medical operations, then after all that sit down to write a surgical board exam—that’s what economists call a barrier to entry. Consequently, not everyone with the dream of becoming a surgeon succeeds, and as a society we’re pretty much okay with this trade-off. In fact, we’re willing to pay good money to ensure that when we walk into a surgeon’s office, the person examining us is almost certainly a seasoned expert and not some high school dropout trying to make a quick buck with knives he bought on eBay.

A parallel system is impossible in music. Nobody dies when a Rachmaninoff concerto is butchered, and if the jazz police fined you for playing Giant Steps without a license, they’d be laughed out of the room. Even if somehow we did manage to create professional barriers to entry in music, it would be a terrible thing. Establishment musicians would undermine any newcomers and we would get a homogeneous musical world built entirely on politics. Case in point: when orchestra auditions started being held behind opaque screens, it significantly boosted the number of female orchestra players, because women were no longer being barred entry based on their gender.

I’ve argued before that music is not a true profession in the full sense of the word, and this is one of the reasons why. Virtually all other professions—from lawyer and accountant to firefighter and electrician—can justify some sort of regulatory system or self-policing that creates barriers to entry. In fact, they need barriers to be effective. Music, on the other hand, is harmed by any such apparatus.

You are probably not an entrepreneur

There is also a good reason musicians and CEOs aren’t paid the same way: entrepreneurship is impossible in art. I’ve written about this in depth before, but let’s look at the issue briefly. An entrepreneur is someone who sees either an unmet need in the market or a more efficient way of meeting a preexisting need, and s/he profits by filling this need en masse in a way that strategically undermines the competition. Entrepreneurial models have to have some form of scalability to succeed, because the offerings need to be both affordable and profitable. They also need to be somewhat exclusive in design so that it’s not trivially easy for others to copy. These are the features that give business executives the leverage to command obscene salaries and so-called “golden parachutes.”

You can build entrepreneurial models around music, yes, but not within music itself. Starting a record label is an entrepreneurial activity (one that used to be a lot more profitable). Similarly, launching a Spotify or a Pandora is an entrepreneurial activity, because there happens to be a market for people to access huge amounts of music via a central online catalog. But it’s the catalog that is the business innovation, not the music, just as distribution and promotion were the innovations of record labels in their heyday. As I’ve argued before, Spotify could just as easily be applied to finding puppy photos if that’s where the market were going—the actual music doesn’t matter.

Founding an ensemble or composing music are not entrepreneurial activities because the models don’t benefit from being scaled up, and they are much too easy to copy. Even if you could release one album per hour or get 10,000 violinists for your orchestra, your music wouldn’t be any more profitable (probably the opposite). Whatever artistic path you take, you’re just adding another drop to the endless sea of music that surrounds us every day. From a business perspective, starting a band is more like creating a cell on a spreadsheet: relatively worthless on its own but of value when collected with other similar bits of data that can be corralled toward a larger purpose. Why? Because entrepreneurship doesn’t give a fuck about qualitative measures of value, it only cares how many units you sell.

So yes, entrepreneurship is a sexy word these days, but it doesn’t apply to art-making. Sidney Shure was an entrepreneur: he recognized a mass market for quality microphones and snagged a huge contract from the US military on the eve of World War II. His SM58 went on to become the most-used microphone of all time. Edward Easton of Columbia Records was an entrepreneur: in 1903 he contracted famous opera singers to record albums, because he figured he might sell more discs if they came with music on them versus the blank media all the other gramophone companies were selling. Columbia remains the longest lived record label in history.

ICE founder Claire Chase, on the other hand, is not an entrepreneur, despite having won a MacArthur Fellowship for it. She is a very talented musician, administrator, organizer, and advocate, but she has not discovered an untapped market nor has she invented a more efficient model for using music nor has she prevented others from copying her model. (In fact, she encourages people to copy it.) Being innovative does not automatically make you an entrepreneur, and the fact that we’ve lost that distinction is part of the problem musicians face.

Video killed the radio star

Art-making lacks certain fundamental elements that define typical professions and businesses. Unfortunately for artists, its accoutrements suffer no such handicap. When you couple technological change with art-making, you begin to see why people will pay $5.00 for a latte but not $0.99 for a song download.

They’re not wrong: $0.99 for a song is too expensive when there’s no value in owning recorded music because you only ever stream it. You can argue that the cost of recording the music justifies a higher price, but that’s irrelevant. In capitalism, the value of something is determined by what people are willing to pay, not by what it costs to produce. If your production costs are too high to turn a profit, you go out of business—that’s how it’s supposed to work. Records and radio hurt the 19th-century sheet music industry. Then amplified music hurt big bands. Then movies hurt opera companies and orchestras, drum machines and sequencers hurt studio musicians, DJs hurt bar and wedding bands, and online streaming is hurting record labels—to the point that Lady Gaga’s recent SXSW performance was sponsored by Doritos, not her label. Meanwhile, music is still music. It’s not like you can enjoy it twice as efficiently by listening to two pieces at once.

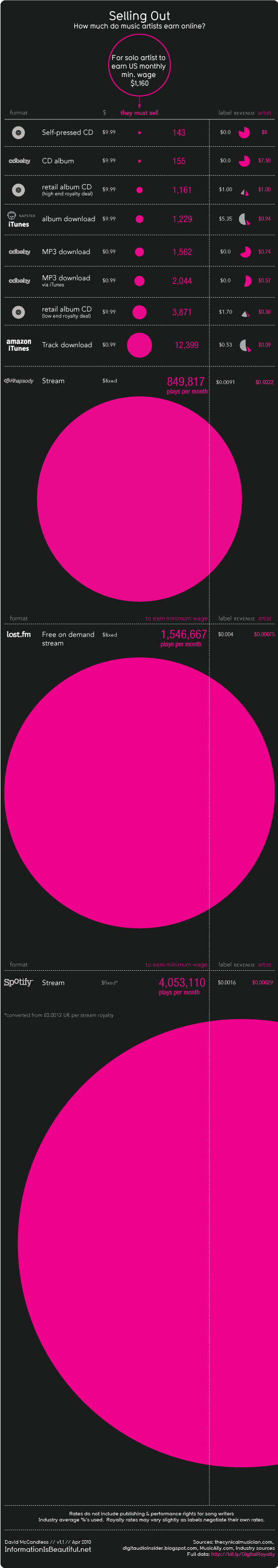

You’ve probably seen this infographic before, showing the number of sales a musician needs in various media to earn the US minimum wage. It’s depressing from the musician’s point of view, but consider it from the music lover’s perspective. There has NEVER been a better time to love music: not only is it cheap, it’s also infinitely easier to explore than in the days of the record megastores. And despite the lack of financial return, somehow new albums keep being made. Maybe that will change someday and the price of music will start to rise, but for now enough music is being recorded to keep the price on a steady march toward zero.

Nor is the live music scene likely to make up for lost recording revenues, because cheap recorded music also pushes down the need for live music. Dave Goldberg’s An Open Letter to Venues That Exploit Their Musicians was a viral hit, and he wasn’t fundamentally wrong in his assertion that venues who pay more for good live music will earn a reputation that boosts their business. But his theory only works in a world where most businesses haven’t figured this out.

Let’s imagine that we live in Goldberg’s ideal world where all venue owners hire good musicians and pay them well. What would happen? Well, most venues would either go out of business or stop presenting live music. For most bar-goers, music is part of the experience, not the defining element. They might enjoy a good live band, but they won’t always be willing to pay a cover charge (or higher drink prices) for the privilege. Sometimes having a conversation with friends will be more important, so they’ll choose musician-free venues except when they’re specifically looking for music. That means venue owners lose the casual crowd—the people who are there for a good time but are not particularly committed to any one venue. Simultaneously, competition for talent among venue owners would increase: the true music lovers would vote with their feet, having come to expect quality entertainment at every venue. That drives up the price of hiring musicians, so fewer venues can afford to do it. Goldberg’s scenario also leads to less opportunity for emerging musicians, since there would be fewer venues to play. The bar scene would begin to resemble the orchestra scene where a handful of top players get all the work and nobody else gets any. Everybody loses, except for the in-crowd musicians.

The end of work

The way musicians are getting squeezed out by technology is not unique to our vocation, although we are on the front line of this trend. Within 10 years, self-driving cars will make the professions of taxi driver, long-haul trucker, and delivery person as antiquated to our kids as travel agents and RadioShack stores are to us. Retail jobs will disappear too, because they won’t be able to compete with online shopping—Amazon is four times more efficient than Walmart, all without resorting to offshored slave labor or threatening the families of union activists. With more and more jobs disappearing, I think the economists predicting the evolution of some sort of guaranteed minimum income are probably right. Earning money—from any occupation—will become less important. Of course, that doesn’t help us much today. But we can be smarter in how we deal with the current challenges.

First, stop lecturing venue owners. If you become famous enough, you’ll be able to command higher fees and that will take care of that. Otherwise, you have to weigh the pros and cons of the gig: is there some other non-financial reason to do it? Try to look at things from the venue owner’s perspective and pitch them an idea that has mutual benefit. “You should change your business model to feature better musicians paid at a higher rate” is not very helpful, but if you propose something doable with a clear win for both sides, you stand a fair chance. I’ve had success with this approach even when negotiating with big companies like Universal Edition over part rental fees. Of course there are also times when it won’t make sense to take the gig—it goes without saying that there are countless poorly run outfits that scrape by simply by offloading their costs onto musicians. These people don’t deserve your time, and no amount of arguing is going to make the gig into something it isn’t.

Second, turn to your “hardcore 4%” to generate the majority of your income. As Jon Nathanson has pointed out, one of the great lessons of Kickstarter is that while the vast majority of your “fans” are willing to contribute exactly zero dollars to you art, about 4% will pay a substantial amount. These are your “hardcore fans,” to use Nathanson’s terminology, and you should charge them a premium for their loyalty. Of course they should get something in return, but your profit margin should be much higher than it is when you’re targeting the lukewarm set. Note that I’m not talking exclusively about crowdfunding here. This principle holds true for philanthropy too: the profit margin on a donors gala should dwarf that of ticket sales. And we all know the raison-d’être of pop music merchandise is to empty the wallets of groupies. Also, if you do go the crowdfunding route, you need to go beyond your circle of musician friends. If your crowdfunding community consists entirely of other musicians who are also mounting Kickstarter projects, you’re not going to get very far.

Third, collaborate with other people. Part of the reason well-paid professions command better terms is that they have organizations that lobby on their behalf and raise awareness for their issues. Maybe it’s the solitary nature of the creative act, but musicians seem singularly adverse to doing anything truly collaborative. There have been a few advocacy efforts, notably Americans for the Arts and the UK-based Featured Artists Coalition, but these are far from household names, even within the arts community. Can you imagine if all the indie bands of the Bay Area founded an organization to lobby the state government on their behalf? The number of professional artists in the USA is about equal to the number of NRA members (and much higher if you include the legions of aspiring artists working at the proverbial Starbucks), yet the gun lobby holds the federal government hostage on any number of issues while arts funding gets slashed with impunity. If we actually lobbied and voted as a block, we could change that. We could push for a yearly music-use tax on all radios and TVs, like what Germany has, or we could sponsor legislation that boosts royalties on music streaming. Even on a smaller scale, we’d get a lot further if we got in the habit of promoting each other’s music, creating a more cohesive “face” for our local scenes, and partnering with non-musical organizations. The “music ghetto” is entirely a product of our own making, and we have no one to blame but ourselves.

Finally, stop wasting energy on “shoulds.” Yes, musicians should be paid better. Yes, the economics of recording should be fairer. Unfortunately, that’s not the world we live in, so stop yakking and go do something about it.